INTRODUCTION

The life expectancy of Koreans has steadily increased due to advancements in medical technology and improved living standards. However, the incidence of chronic diseases has risen due to factors such as stress, irregular eating habits, sleep disorders, and sedentary lifestyles. In particular, circulatory diseases and cancer have shown a marked increase, which is closely associated with metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome is defined as a cluster of metabolic abnormalities, including abdominal obesity, hypertension, hyperglycemia, elevated triglycerides, and low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels, and is known to significantly increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases and diabetes [

1,

2].

Over the past two decades, the prevalence of metabolic syndrome among Korean adults has increased from 27.1% to 33.2%. The rise has been particularly dramatic in male, where prevalence surged from 25.8% to 40.0%, primarily driven by increased abdominal obesity and hyperglycemia. These findings underscore the importance of early detection and prevention of metabolic syndrome [

3].

Mental health and lifestyle factors play critical roles in the onset of metabolic syndrome, with sleep duration being a particularly important variable. Short sleep duration can stimulate the sympathetic nervous system, leading to increased heart rate and blood pressure, elevated secretion of cortisol—a stress hormone—and the exacerbation of insulin resistance and metabolic abnormalities [

4-

6]. Studies suggest that the relationship between sleep duration and the prevalence of metabolic syndrome follows a U-shaped curve, with both short and long sleep durations posing risks [

7-

9].

In female, menopause induces significant metabolic changes, increasing the risk of abdominal obesity, elevated triglycerides, and hyperglycemia. Consequently, the prevalence of metabolic syndrome rises sharply in postmenopausal female. This highlights the need for studies analyzing the relationship between sleep duration and metabolic syndrome while considering sex and physiological conditions [

10,

11].

This study utilized data from the 8th Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) to examine the association between sleep duration and the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Korean adults. Specifically, it assessed the risks of short sleep duration (<6 hours) in male and compared the prevalence of individual metabolic syndrome components between premenopausal and postmenopausal female. The findings aim to provide a foundation for the development of preventive and management strategies for metabolic syndrome that account for sex and physiological differences.

METHODS

Study population

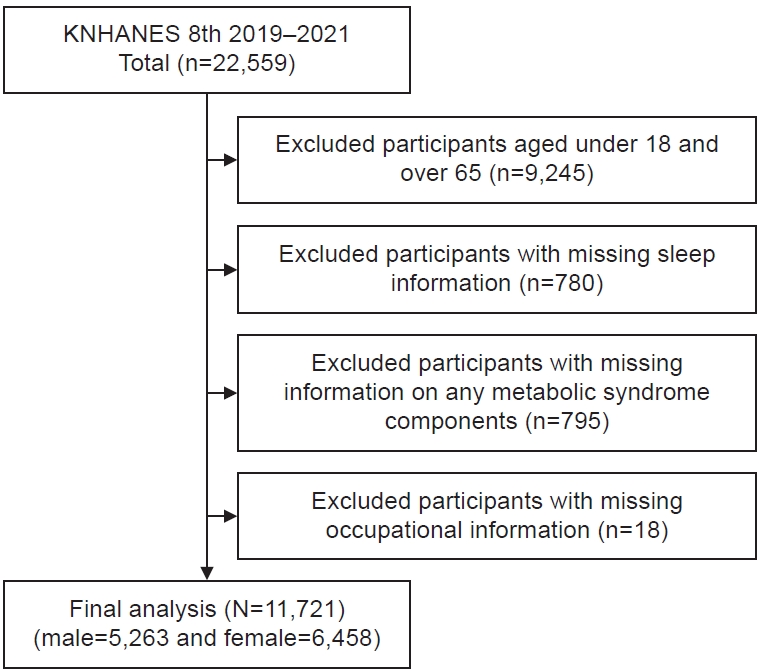

This study was conducted using data from the 8th KNHANES (2019–2021). Of the 22,559 participants in the KNHANES, individuals aged 18 years or younger and those aged 65 years or older (n=9,245) were excluded. Consequently, 13,314 adults aged 19 to 64 years were initially selected for analysis. Among these, 780 participants with missing data on sleep duration and 795 individuals with incomplete information required for the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome-such as blood pressure, blood glucose, triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, or waist circumference-were excluded. Additionally, 18 participants with missing occupational data were removed. Ultimately, a total of 11,721 participants (5,263 male and 6,458 female) were included in the final analysis (

Fig. 1).

Variable definitions

Dependent variable

The dependent variable in this study was metabolic syndrome, defined based on the revised 2005 National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel-III criteria and the waist circumference thresholds suggested by the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity [

12].

Metabolic syndrome was diagnosed if an individual met three or more of the following five criteria:

ㆍAbdominal obesity: Waist circumference ≥90 cm for male and ≥85 cm for female.

ㆍHypertriglyceridemia: Triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL or currently taking medication for dyslipidemia.

ㆍHypertension: Systolic blood pressure ≥130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥85 mmHg, or currently taking antihypertensive medication.

ㆍLow HDL cholesterol: HDL cholesterol <40 mg/dL for male and <50 mg/dL for female.

ㆍHyperglycemia: HbA1C ≥5.7% was used as an indicator instead of fasting blood glucose, and individuals taking diabetes medication were also included [

13].

Independent variable

The independent variable was average daily sleep duration, measured based on the “weekday sleep duration” item from the Mental Health section of the KNHANES (2019–2021). Participants were asked to report their average bedtime and wake-up time on weekdays, and these were used to calculate their daily sleep duration. For this study, sleep duration was categorized into three groups:

ㆍShort sleep duration: Less than 7 hours.

ㆍOptimal sleep duration: 7 hours to less than 9 hours.

ㆍExcessive sleep duration: 9 hours or more [

14,

15].

For male, a further stratification was made to analyze the impact of very short sleep duration (<6 hours) on the risk of metabolic syndrome. This additional classification (less than 6 hours, 6 to less than 7 hours, 7 to less than 9 hours, and 9 hours or more) aimed to provide a more precise understanding of how short sleep duration affects the components of metabolic syndrome in male.

This classification was based on prior studies reflecting the characteristics of the Korean population and the guidelines recommended by the National Sleep Foundation in the United States [

16].

Covariates

a. Sociodemographic Characteristics: Sociodemographic characteristics included sex, age, income level, and educational attainment, all of which were self-reported. Age was categorized into five groups based on the KNHANES data: 19–29 years, 30–39 years, 40–49 years, 50–59 years, and 60–64 years. Marital status was classified as “single,” “married,” or “without a spouse” (separated, divorced, or widowed). Educational attainment was grouped into four categories: “elementary school graduate or lower,” “middle school graduate,” “high school graduate,” and “college graduate or higher.” Income level was divided into four groups: “high,” “upper middle,” “lower middle,” and “low.”

b. Health Behavior Characteristics: Health behavior characteristics included smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, sleep duration, and obesity. Smoking status was classified into “non-smoker,” “former smoker,” and “current smoker,” with non-smokers defined as those who had smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime. Alcohol consumption was grouped into three categories: “less than once per month,” “1–4 times per month,” and “twice or more per week.” Physical activity was assessed based on the weekly accumulation of at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity. Obesity was defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥25 kg/m2. For female, menopausal status (absence of menstruation for 12 consecutive months) was also considered.

c. Occupational Characteristics: Occupational characteristics included shift work status and average weekly working hours. Shift work was classified as either “daytime work” or “shift work.” Daytime work referred to jobs performed exclusively during regular daytime hours, while shift work included evening work, night work, rotating shifts (including day and night rotations), 24-hour shifts, split shifts, irregular shifts, and any work schedule involving nighttime or non-daytime hours. Average weekly working hours were categorized as “40 hours or fewer” and “more than 40 hours.”

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 29.0 (IBM Corp.), and the significance level was set at P<0.05. The specific analytical methods employed in this study were as follows:

First, descriptive statistics were performed to examine the general and health behavior characteristics of the study population. Frequencies and percentages were presented for categorical variables, while means and standard deviations were reported for continuous variables.

Second, chi-squared tests (χ2-tests) were used to assess differences in the prevalence and statistical significance of metabolic syndrome and its components across sleep duration categories.

Third, logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the effect of sleep duration on the prevalence of metabolic syndrome. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to quantify the associations.

Ethics statement

This study was exempted from approval by the Institutional Review Board because this study was a secondary data analysis of existing data.

RESULTS

Metabolic syndrome by general characteristics

This study analyzed the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its associated factors among 5,263 male and 6,458 female. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome was 34.4% in male and 23.6% in female, and it increased with age. The highest prevalence was observed in the 60–64 age group, with rates of 50.6% in male and 54.4% in female.

Shorter sleep duration was associated with a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome. Among those sleeping less than 6 hours per night, the prevalence was 43.6% in male and 29.9% in female. Additionally, the prevalence of metabolic syndrome was significantly higher in individuals who were obese, had lower educational attainment, lower income, or no spouse. Lifestyle factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, shift work, and working more than 40 hours per week were also associated with increased prevalence.

Among individuals who did not engage in regular exercise, the prevalence of metabolic syndrome was 39.1% in male and 25.8% in female. Obese individuals exhibited the highest prevalence, with 56.5% in male and 56.3% in female (

Table 1).

Metabolic syndrome by sleep duration

In male, shorter sleep duration was associated with a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome. The prevalence was 37.8% in male sleeping less than 7 hours, 31.9% in those sleeping 7 to less than 9 hours, and 28.5% in those sleeping 9 hours or more (P<0.001). Abdominal obesity was most prevalent in male sleeping less than 7 hours (43.5%), followed by those sleeping 7 to less than 9 hours (37.1%) and those sleeping 9 hours or more (37.9%) (P<0.001). Similarly, hyperglycemia was most prevalent in male sleeping less than 7 hours (44.9%), compared to 40.4% in those sleeping 7 to less than 9 hours, and 29.6% in those sleeping 9 hours or more (P<0.001).

In female, shorter sleep duration was also associated with a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome. The prevalence was 26.6% in female sleeping less than 7 hours, 21.8% in those sleeping 7 to less than 9 hours, and 18.7% in those sleeping 9 hours or more (

P<0.001). Abdominal obesity was most prevalent in female sleeping less than 7 hours (29.9%), followed by those sleeping 9 hours or more (24.7%) and those sleeping 7 to less than 9 hours (22.6%) (

P<0.001). Hyperglycemia was also most prevalent in female sleeping less than 7 hours (42.1%) (

P<0.001) (

Table 2).

Relationship between sleep duration and metabolic syndrome

Association between sleep duration and metabolic syndrome and its components

Logistic regression analysis revealed that in male, insufficient sleep (less than 7 hours) was associated with a 1.27-fold higher risk of metabolic syndrome (95% CI: 1.12–1.43) and a 1.29-fold higher risk of abdominal obesity (95% CI: 1.15–1.45) compared to optimal sleep duration (7 to less than 9 hours).

In female, insufficient sleep increased the risk of abdominal obesity by 1.34 times (95% CI: 1.19–1.52), but no significant association was observed with the overall risk of metabolic syndrome (

Table 3).

Insufficient sleep was a significant common factor associated with increased risk of abdominal obesity in both male and female.

Association between metabolic syndrome and categorized sleep duration in male

When sleep duration was further categorized, male sleeping less than 6 hours exhibited a 1.54-fold higher risk of metabolic syndrome (95% CI: 1.30–1.82) compared to those with optimal sleep (7 to less than 9 hours). Additionally, this group showed the highest risk of abdominal obesity, with a 1.51-fold increase (95% CI: 1.29–1.77) (

Table 4).

Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its components before and after menopause

Postmenopausal female exhibited a metabolic syndrome prevalence of 41.3%, approximately 2.8 times higher than the 14.5% observed in premenopausal female. Among its key components, abdominal obesity increased from 20.5% before menopause to 35.9% after menopause, hypertension from 14.8% to 43.3%, and hyperglycemia from 24.2% to 64.3% (all

P<0.001) (

Table 5).

Notably, the prevalence of hyperglycemia showed the largest increase, with postmenopausal female exhibiting a prevalence approximately 2.7 times higher than premenopausal female.

Association between sleep duration and metabolic syndrome in premenopausal and postmenopausal female

Logistic regression analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between sleep duration and metabolic syndrome and its components in premenopausal and postmenopausal female (

Table 6).

In premenopausal female, insufficient sleep (less than 7 hours) was associated with a 1.28-fold higher risk of metabolic syndrome (95% CI: 1.06–1.55) and a 1.41-fold higher risk of abdominal obesity (95% CI: 1.20–1.66) compared to optimal sleep duration (7 to less than 9 hours).

In postmenopausal female, insufficient sleep was associated with a 1.26-fold higher risk of abdominal obesity (95% CI: 1.05–1.52) compared to optimal sleep.

In both premenopausal and postmenopausal female, insufficient sleep significantly increased the risk of abdominal obesity. However, the risk of metabolic syndrome increased with insufficient sleep only in premenopausal female.

DISCUSSION

This study analyzed the relationship between sleep duration and metabolic syndrome, considering sex and menopausal status, using data from the 8th Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES, 2019–2021). The main findings revealed that shorter sleep duration significantly increased the risk of metabolic syndrome in male, with the highest risk observed in those sleeping less than 6 hours. Among female, the association between sleep duration and the components of metabolic syndrome differed based on menopausal status. These findings suggest that sleep duration is a critical factor in the development of metabolic syndrome and highlight the study’s novelty in providing more detailed analysis by sex and physiological state compared to previous studies.

Shorter sleep duration increases the risk of metabolic syndrome due to physiological mechanisms such as sympathetic nervous system hyperactivation, increased cortisol secretion, and worsened insulin resistance. These mechanisms are well-documented in the literature and support this study’s results that short sleep is associated with increased risks of metabolic abnormalities and abdominal obesity [

1,

6]. In particular, this study further subdivided male participants into a group sleeping less than 6 hours, revealing that very short sleep durations significantly exacerbate the risk of metabolic syndrome. Unlike most prior studies that dichotomized sleep duration into “short” and “adequate,” this study offers insights into the specific risks posed by extremely short sleep durations [

3,

4].

The rapid increase in the risk of metabolic syndrome in postmenopausal female is primarily attributed to decreased estrogen levels, which lead to changes in fat distribution and worsened insulin sensitivity. This study showed that premenopausal female with shorter sleep durations (<7 hours) had a 1.41-fold increased risk of abdominal obesity, while postmenopausal female exhibited a similar trend with a 1.26-fold increased risk. Notably, postmenopausal female demonstrated higher prevalence rates of metabolic syndrome components such as abdominal obesity, hypertension, and hyperglycemia. These findings suggest that short sleep durations can exacerbate metabolic abnormalities in postmenopausal female [

7,

8].

The observed prevalence of hyperglycemia in postmenopausal female is particularly noteworthy. This increase reflects physiological changes in postmenopausal female, such as worsened insulin resistance and impaired glucose regulation. Previous studies have identified these changes as major contributors to the heightened risk of metabolic syndrome in postmenopausal female. This study builds on these findings, demonstrating that short sleep durations may further increase the risk of hyperglycemia in this population. These results emphasize the importance of developing tailored preventive strategies for metabolic syndrome in postmenopausal female [

9,

10].

Compared to previous studies, this research has several significant strengths. First, it analyzed the relationship between sleep duration and metabolic syndrome by accounting for sex and menopausal status. While most prior studies either broadly examined the relationship or only divided participants by sex, this study provides a detailed comparison of metabolic syndrome prevalence rates and component-specific risks based on premenopausal and postmenopausal status. Second, it subdivided male’s sleep durations to include a group sleeping less than 6 hours, providing a more precise analysis of the risks associated with very short sleep durations. This contrasts with prior studies that often defined short sleep as less than 7 hours. Third, this study used data from KNHANES, ensuring large-scale representativeness and high reliability through the use of the most recent data.

The findings of this study offer several important implications. First, for male, extremely short sleep durations (less than 6 hours) significantly increase the risk of metabolic syndrome. This highlights the need for education and interventions aimed at maintaining adequate sleep duration (7–9 hours). Second, for female, the risk factors for metabolic syndrome vary before and after menopause. Tailored management strategies considering menopausal status are essential, especially for postmenopausal female, where increased fat accumulation and decreased insulin sensitivity are major contributors to metabolic abnormalities. Third, this study demonstrates the importance of detailed categorization of sleep durations in assessing the risk of metabolic syndrome. Future studies should move beyond simple dichotomization of “short” and “long” sleep durations to include more precise classifications of very short sleep.

Despite its strengths, this study has several limitations. First, sleep duration was self-reported, which may lead to recall bias or under- or over-reporting. Second, this study focused solely on sleep duration without accounting for qualitative factors such as sleep disorders (e.g., insomnia, sleep apnea) or stress levels, which may influence the results. Third, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to determine causal relationships between sleep duration and metabolic syndrome. Future research should adopt longitudinal designs to address these limitations and incorporate multidimensional analyses, including qualitative assessments of sleep.

In conclusion, this study confirms that sleep duration significantly impacts the risk of metabolic syndrome and highlights the differences by sex and menopausal status. These findings provide critical evidence for the development of tailored strategies for the prevention and management of metabolic syndrome based on sex and physiological state.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print