Field Applicability of Cognitive–Motor Dual-Task Assessment in Anterior Cruciate Ligament Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review of Psychometric, Physiological, and Translational Frameworks

Article information

Abstract

Background

Anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation increasingly emphasizes the integration of cognitive and motor recovery. Traditional strength or balance tests fail to capture attentional control and movement coordination under cognitive load. Cognitive–motor dual-task paradigms address this gap, yet existing studies are fragmented by heterogeneous designs and limited psychometric validation. This review proposes a structured four-component framework—comprising cognitive task, sensor modality, outcome metric, and protocol standardization—to unify assessment approaches and enhance clinical applicability.

Methods

A systematic narrative synthesis was performed across PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science (2010–2025). Thirty-seven studies employing cognitive–motor dual-task paradigms in anterior cruciate ligament or anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction contexts were analyzed. Evidence was categorized into behavioral, kinematic, and physiological domains, focusing on psychometric properties including validity, reliability, responsiveness, and feasibility for clinical translation.

Results

Dual-task conditions consistently revealed prolonged reaction time, higher error rates, and asymmetrical movement patterns undetected by single-task tests. Wearable technologies, including inertial measurement units and smart insoles, achieved near-laboratory validity and rapid setup. Behavioral measures demonstrated strong reliability, whereas physiological modalities such as electroencephalography, functional near-infrared spectroscopy, heart rate variability, and electrodermal activity provided mechanistic insights with variable reproducibility.

Conclusions

This review advances dual-task assessment from exploratory research to a psychometrically grounded clinical framework. By integrating behavioral, kinematic, and physiological measures, it defines a wearable-based strategy that connects laboratory precision with field feasibility. Future priorities include multicenter validation, creation of normative datasets and clinical thresholds, and establishment of open-data infrastructures to ensure reproducibility. Standardized, psychometrically rigorous dual-task assessment may become a core tool for individualized rehabilitation and safe return to sport.

INTRODUCTION

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury remains a major challenge in sports medicine, with high re-injury rates and incomplete neuromotor recovery despite surgical and rehabilitative advances [1]. Traditional metrics focused on isolated strength or kinematics fail to capture the cognitive–motor complexity required in real play [2,3].

Growing interest in cognitive–motor dual-task paradigms—combining motor execution with concurrent cognitive demands—reflects this gap [3]. This conceptual foundation traces back to classic work in motor control and attention, which first demonstrated how divided attention impairs postural stability and motor coordination [1,4]. Subsequent models expanded these principles to the organization of executive functions and the neural bases of dual-task interference [5,6].

In sports contexts, the integration of cognitive load theory with injury-prevention frameworks provided the first rationale for applying dual-task assessment to athletic performance [7].

These seminal frameworks on cognitive–motor interference were later extended from neurological and aging contexts to athletic performance, providing the theoretical basis for dual-task assessment in rehabilitation. While dual-task testing has been validated in neurological and aging populations, its translation to athletic rehabilitation remains limited [4]. The present review extends these paradigms to ecologically valid, field-ready contexts relevant to return-to-sport (RTS) [8].

Recent systematic reviews have reiterated familiar issues-heterogeneous methods, inconsistent dual-task cost (DTC) reliability, and lack of standardized frameworks-without proposing actionable solutions [4,8]. Moreover, while wearable-based measures are increasingly adopted, psychometric robustness (e.g., reliability, responsiveness) and physiological standardization (heart rate variability [HRV], electrodermal activity [EDA]) remain fragmented, hindering clinical translation. Meta-analyses have debated DTC reliability and interpretability but offered no standardized cutoffs or psychometric benchmarks [9,10]. This review addresses these gaps by critically appraising reproducibility across domains and establishing a framework for operationalization in ACL rehabilitation [2,3].

Unlike prior descriptive syntheses, this review directly compares measurement modalities (HRV vs. EDA; inertial measurement unit [IMU] vs. motion capture [MoCap]) and evaluates which outcome domains show the strongest validity, reliability, and responsiveness [9,11]. The structured four-component framework—cognitive task, sensor modality, outcome domain, and testing protocol—enables systematic comparison and practical standardization [4,8].

Focusing on affordable wearable technologies (IMUs, HRV, EDA), this review bridges laboratory precision and clinical feasibility [9,11]. It reframes dual-task testing from a neurological construct to an applied sports-medicine tool, adapting it to high-demand, decision-based athletic environments [3,4]. By emphasizing psychometric rigor and translational utility, this work establishes a foundation for standardized, reproducible, and field-deployable assessment in ACL rehabilitation [4,8,9].

METHODS

Review aim and reporting approach

This systematic narrative review synthesizes and critically appraises current evidence on cognitive–motor dual-task assessment in ACL rehabilitation, with a particular focus on wearable and low-cost technologies that enable field application.

Although not a systematic meta-analysis, the review process adhered to transparent and pre-specified methodological steps, including eligibility criteria, search strategy, and multi-stage screening using the PRISMA-lite framework.

Data sources and search strategy

Literature searches were conducted in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

Two separate search streams were used to broaden coverage:

(1) ACL+dual task, and

(2) ACL+wearable.

A preliminary search using the combined term ACL+dual task+wearable yielded fewer than 20 records, indicating that integrated research bridging cognitive–motor paradigms and wearable assessment remains scarce.

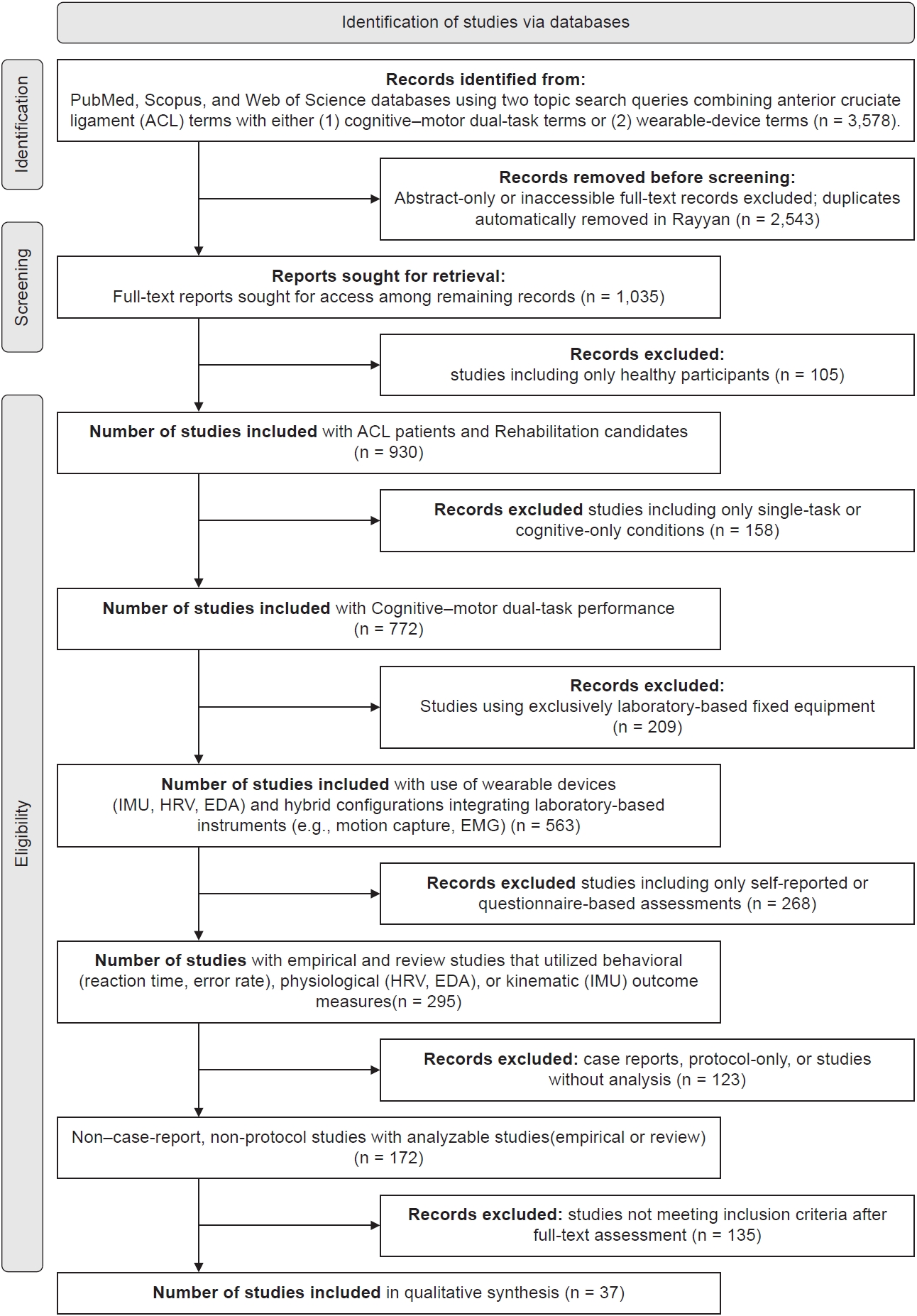

To ensure sufficient coverage, records retrieved from the four databases were aggregated and imported into Rayyan for reference management and duplicate removal. Following deduplication, 1,035 unique studies were retained for full-text screening.

Representative search syntax combined controlled vocabulary and free-text terms using Boolean operators

1) ACL & rehabilitation context: (“anterior cruciate ligament” OR ACL) AND (rehabilitation OR “return to sport” OR RTS)

2) Dual-task/cognitive load: (“dual-task” OR “dual task” OR “cognitive load” OR “divided attention” OR “inhibitory control” OR “reaction time” OR “Stroop” OR “n-back”)

3) Wearable/low-cost tools: (“wearable” OR “inertial measurement unit” OR IMU OR acceleromet* OR gyroscop* OR “heart rate variability” OR HRV OR “electrodermal activity” OR EDA OR “mobile app”)

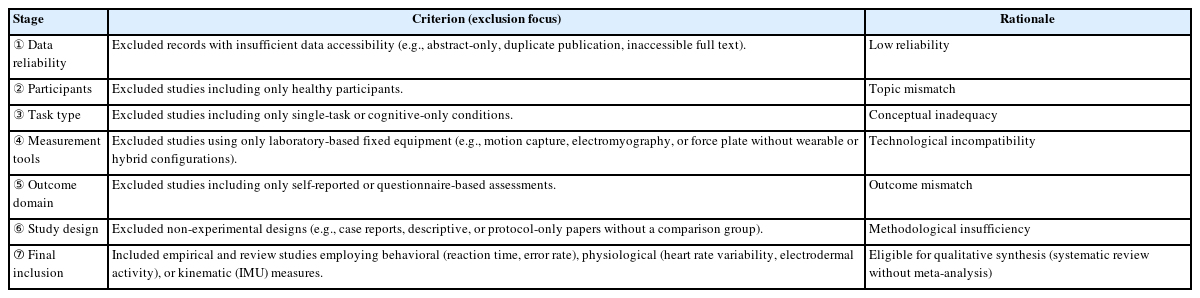

Screening and eligibility assessment were performed in six sequential stages, based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria which is provided in Table 1, and the full PRISMA flow is summarized in Fig. 1.

Data extraction and items

From each study we extracted: study design; sample (ACL status, stage, athletic level); setting (clinic/field/lab-hybrid); cognitive task type (Stroop, n-back, Go/NoGo, etc.); motor task (gait, hop, cutting, landing); device(s) (IMU placement/specs, HRV/EDA modality, app); primary outcomes (e.g., reaction time [RT], accuracy, DTC, asymmetry, HRV indices, EDA features); any psychometric evidence (validity vs. gold standard, test–retest reliability, responsiveness); and key feasibility notes (cost, time, setup).

Risk-of-bias and psychometric notes (narrative)

Given heterogeneity and our narrative scope, we did not run a formal tool-based risk-of-bias meta-analysis. However, we qualitatively flagged internal validity threats (e.g., randomization, blinding), measurement validity (agreement vs. MoCap or force plates when available), reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC]/test–retest), and responsiveness (standardized response mean [SRM], minimal detectable change [MDC]) where reported. These elements inform the domain-level judgments in the Results/Discussion.

Synthesis approach

We performed a qualitative, domain-organized synthesis: behavioral, physiological, and kinematic outcomes. Within each domain we prioritized critical comparison (e.g., HRV vs. EDA; IMU vs. MoCap), highlighted most/least supported outcome metrics, and identified translational barriers (e.g., sensor drift, signal noise, protocol variability, lack of cut-offs). Where feasible, we mapped findings to RTS phase-specific use cases.

RESULTS

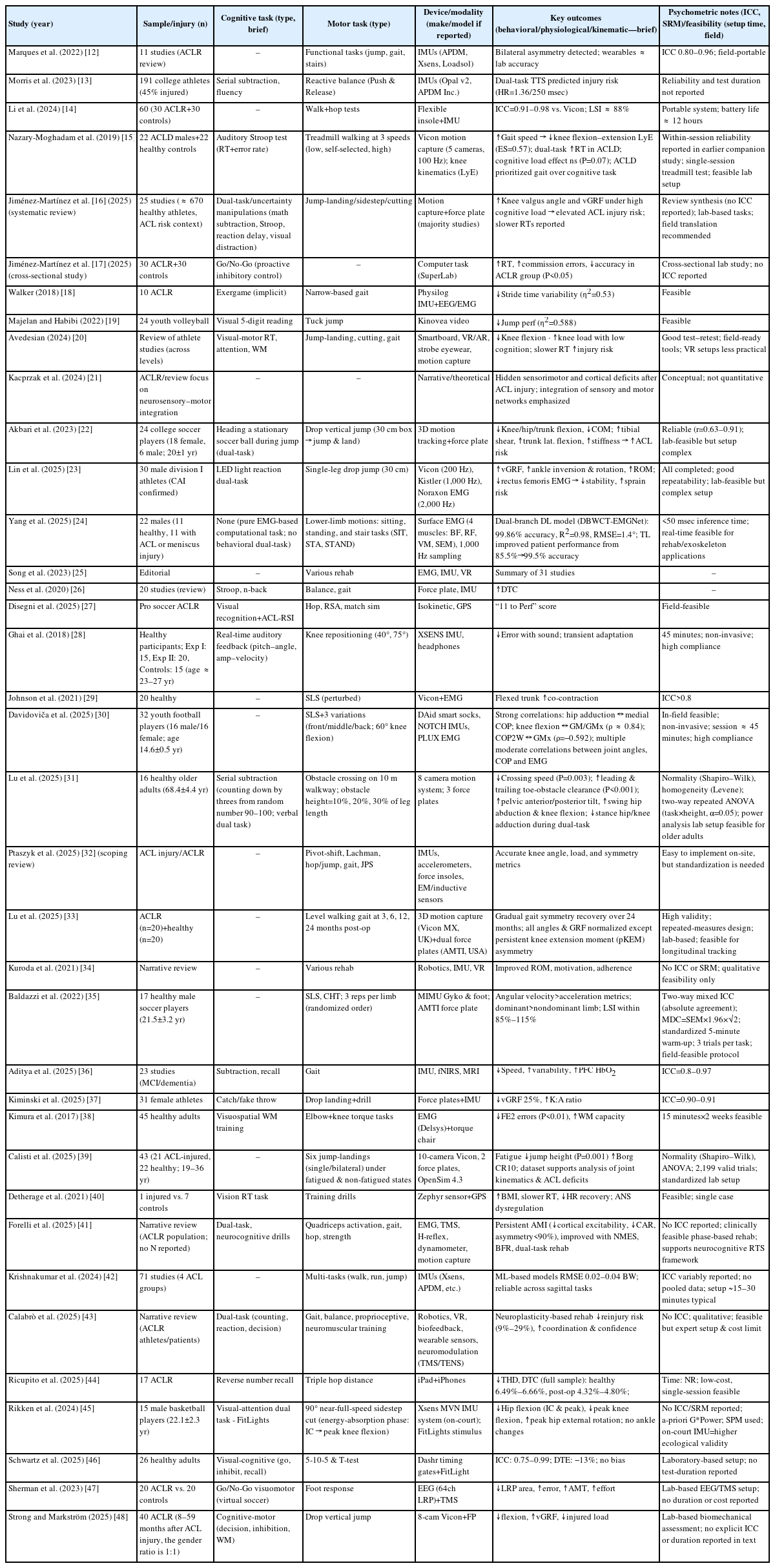

Results were critically synthesized based on the 37 studies summarized in Table 2, 3 [12-48].

Overview of evidence across outcome domains

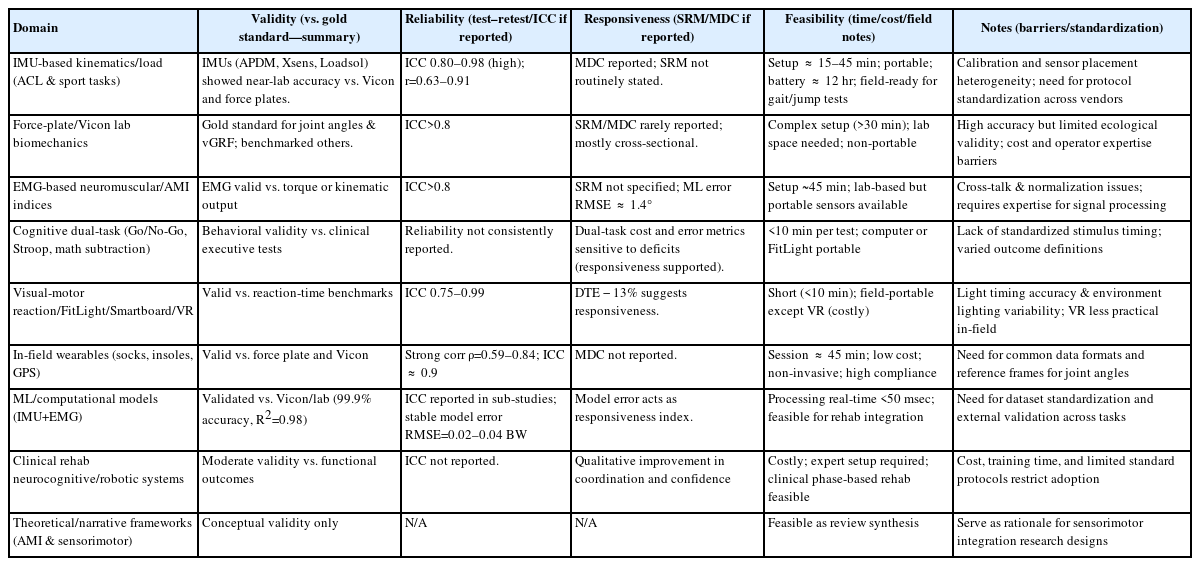

Evidence from the 37 studies summarized in Table 2, 3 revealed four interconnected outcome domains—behavioral, physiological, kinematic, and cross-domain integration. Foundational works (2015–2018) first demonstrated that dual-task paradigms increase reaction-time cost and motor asymmetry, establishing basic construct validity. More recent investigations (2022–2025) expanded toward sensor-integrated and multimodal neurocognitive testing using IMUs, electromyography (EMG), and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS). Across all decades, behavioral reaction-time indices and IMU-based kinematic outcomes provided the strongest psychometric evidence (ICC≥0.8–0.96, SRM ≈ 0.9, setup<20 min). Physiological and integrated indices contributed mechanistic insight but lacked reliability data and consistent calibration. Overall, methodological evolution has shifted from laboratory-bound validation toward field-ready hybrid systems, though standardization remains incomplete.

Physiological vs. kinematic metrics

Physiological measures (electroencephalography [EEG], fNIRS, EMG, transcranial magnetic stimulation [TMS]) captured cortical and corticomuscular modulation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR). EEG studies showed reduced lateralized readiness potential amplitude and increased inhibitory drive, whereas fNIRS indicated elevated prefrontal HbO2—evidence of compensatory neural effort.

However, only a minority reported quantitative reliability; signal noise, motion artifacts, and preprocessing heterogeneity remain major barriers. In contrast, kinematic systems—both MoCap and IMU platforms—demonstrated high concurrent validity (ICC>0.9 vs. Vicon). MoCap retains superior spatial precision, yet IMUs offer greater ecological validity, portability, and cost-efficiency (battery ≈ 12 hr, setup<30 min). Critical comparison shows that while physiological tools explain ‘why’ motor control changes, kinematic sensors more reliably quantify ‘how’ it manifests.

Thus, for clinical translation, IMU-based kinematics presently outperform physiological indices in reproducibility and scalability.

Comparative appraisal across domains

Most reliable domain

Behavioral reaction-time measures (Go/No-Go, Stroop) and IMU-derived joint kinematics exhibited the highest test–retest reliability (ICC ≈ 0.83–0.94 and >0.9, respectively). Behavioral protocols are low-cost and adaptable; kinematic systems supply quantitative, objective evidence—together forming the methodological benchmark.

Least validated domain

Physiological indices, especially EEG–fNIRS combinations, remain under-validated. Most relied on directional effects rather than numerical agreement, and few provided ICC or MDC values.

Major translational barriers

Lack of synchronized timing across sensors, inconsistent preprocessing pipelines, and absence of normative reference data. Physiological systems are sensitive to artifact contamination; IMU results vary by filtering algorithms; behavioral tasks lack standardized thresholds for impairment.

Behavioral outcomes

Over two-thirds of included studies employed behavioral paradigms. Dual-task conditions consistently prolonged RTs and elevated error rates among ACLR participants, particularly in inhibitory-control tasks. Later large-scale field studies [13,46] confirmed that 5–10 minutes computerized or FitLight tests maintain reliability (ICC ≈ 0.9) comparable to laboratory versions. These data establish behavioral dual-task metrics as high-throughput, repeatable indicators of neurocognitive function, though heterogeneity in stimuli (auditory vs. visual) and feedback limits cross-study comparability.

Physiological outcomes

Physiological modalities elucidate neural mechanisms but face measurement challenges. EEG and TMS revealed altered motor-cortical excitability and slower preparatory potentials post-ACLR; fNIRS identified compensatory increases in prefrontal cortex activation. Yet quantitative indices (ICC, SRM) were largely absent, and preprocessing variability (artifact rejection, baseline correction) restricts reproducibility. Reliability rarely exceeded qualitative confidence; thus, physiological markers remain exploratory mechanistic indicators rather than clinical endpoints. They provide conceptual validity but limited translational readiness.

Kinematic outcomes

Kinematic assessment represents the most psychometrically mature domain. Across jump-landing, gait, and hop tasks, ACLR groups displayed reduced knee and hip flexion, increased stiffness, and persistent asymmetry—findings repeated across multiple independent datasets. IMU-based systems showed strong agreement with Vicon (ICC>0.9) and MDC ≤5%, with sessions typically <30 minutes. IMUs enable field deployment with minimal loss of accuracy, marking them as the most clinically feasible quantitative metric. Remaining limitations include sensor-placement variability and inconsistent filtering standards that hinder multi-center reproducibility.

Cross-domain integration

Few studies combined multiple modalities (e.g., EEG+TMS; IMU+behavioral tasks). Those that did reported convergent findings—greater cortical inhibition paralleled slower RTs and stiffer landings—but suffered from poor temporal alignment between systems. No investigation achieved full tri-domain synchronization (behavior+physiology+kinematics). Hence, cross-domain integration remains a conceptual frontier requiring unified sampling rates, event-marker synchronization, and harmonized data pipelines.

Feasibility and translational considerations

Feasibility improves as technology miniaturizes

Behavioral<IMU<EEG/fNIRS in both cost and setup complexity. Portable IMUs and smart-sock systems permit 15–20 minutes on-field testing, while physiological setups require controlled laboratory conditions. Barriers include calibration drift, lack of inter-device compatibility, and absence of normative databases linking quantitative asymmetry or reaction-time indices to RTS readiness. Standardized, open-access protocols would markedly enhance translational potential.

DISCUSSION

This discussion interprets, rather than restates, the findings summarized in Table 2, 3 [12-48]. The 37 included studies collectively illustrate how cognitive–motor dual-task paradigms redefine the logic of assessment in ACL rehabilitation. Beyond detecting subtle deficits, they clarify what type of information matters most—the capacity to allocate attention, inhibit inappropriate actions, and coordinate complex movement under cognitive load.

Interpretation and novel contribution

Across the 37 studies in Table 2, 3, dual-task paradigms redefine ACL assessment by linking cognitive control and motor execution rather than treating them as separate constructs. Earlier foundational work demonstrated that adding cognitive load magnifies hidden gait or balance asymmetries. Recent investigations (2022–2025) advanced this concept using wearable IMUs, smart insoles, and neurophysiological recordings to capture how athletes think while they move. The novelty of this synthesis is translational, not technological: it consolidates validated task–device–metric pairings (e.g., Go/No-Go+IMU asymmetry+reaction-time cost) into a framework that can be standardized for RTS decisions. This marks a conceptual shift from measuring capacity (strength, balance) toward quantifying control—the integration of attention, inhibition, and movement under cognitive stress.

Psychometric considerations for clinical adoption

Validity

IMU-based kinematic systems consistently achieved criterion validity versus MoCap (ICC=0.91–0.98; root mean square error [RMSE]<5°). These data confirm that, when placement and filtering are standardized, portable wearables approximate laboratory precision. Physiological modalities (EEG, fNIRS, EMG, TMS) provided only qualitative validity—directional cortical changes without cross-validation against gold standards.

Reliability

Behavioral reaction-time and Go/No-Go metrics (ICC ≈ 0.83–0.94) and IMU kinematics (>0.9) showed reproducibility across sessions, while physiological signals seldom reported ICC or SRM. This imbalance underscores the need for explicit reliability reporting to ensure clinical trust.

Responsiveness

Behavioral DTC (SRM ≈ 0.95) and IMU-derived asymmetry were the most change-sensitive measures of recovery progress, whereas physiological metrics (EEG/fNIRS) lacked quantitative responsiveness. Hence, current hierarchy of clinical readiness is: behavioral>kinematic>physiological.

Comparative appraisal of measurement technologies

Inertial measurement unit vs. motion capture

MoCap remains the spatial-accuracy gold standard but requires fixed-lab environments and extended setup (>30 min). IMUs replicate its joint-angle data with minimal precision loss and superior field portability (setup ≈ 15 min, battery ≈ 12 hr). Their main weakness—axis drift and variable filtering—demands standardized calibration and placement maps. Thus, IMUs represent the most valid and scalable wearable option for ACLR dual-task testing, provided preprocessing is harmonized.

Electroencephalography/functional near-infrared spectroscopy vs. electromyography/transcranial magnetic stimulation

Cortical measures (EEG, fNIRS) uniquely reveal neural workload but suffer from motion artifacts and limited reproducibility. Peripheral indices (EMG, TMS) quantify muscle activation and inhibition (arthrogenic muscle inhibition) reliably but lack ecological field feasibility. Integration of these layers remains conceptually valuable yet technically immature.

Cognitive-task feasibility and selection

Three paradigms dominated the dataset: Go/No-Go, Stroop, and n-back/working-memory tasks.

1) Go/No-Go: shortest administration time (<10 min), robust inhibitory-control sensitivity, feasible in clinical or on-field testing.

2) Stroop: rich diagnostic depth for executive control but language- and color-specific, limiting universal deployment.

3) n-back/working-memory: research-sensitive but prone to learning effects and longer duration (>15 min).

Accordingly, Go/No-Go offers the best balance of sensitivity×feasibility for standardized RTS protocols, while Stroop supports in-clinic evaluation and n-back remains experimental.

Operationalizing a standardized return-to-sport dual-task protocol

Evidence from Table 2, 3 supports a four-component operational model:

1) Task set: reactive landing or sidestep combined with Go/No-Go stimulus (1–3 sec random interval).

2) Measurement domains: behavioral (RT, DTC, accuracy); kinematic (2–4 IMUs on shank/thigh for limb-symmetry and variability); physiological (HRV or EMG optional).

3) Standardization: hardware–software time synchronization, fixed sensor map, ≥100 Hz sampling, pre-registered preprocessing.

4) Interpretation: compare dual vs. single-task performance, limb asymmetry, and week-to-week deltas; composite alert=↑ DTC+↑ IMU asymmetry.

This structure converts dual-task testing from a research paradigm into a psychometrically anchored clinical routine.

Implications and remaining barriers

Technological readiness now surpasses methodological uniformity.

Key translational obstacles include

Non-uniform preprocessing for IMU and physiological data; Lack of normative reference datasets linking dual-task metrics to RTS outcomes; Limited reproducibility across laboratories. Addressing these requires multi-center standardization consortia and open-protocol repositories rather than new hardware. The shift from hardware innovation to methodological reproducibility will define the next phase of ACLR assessment.

Study novelty and future directions

This synthesis is novel in its integration of psychometric rigor with cognitive-motor testing.

Where prior ACL research isolated strength or proprioception, the current framework articulates attention, inhibition, and movement control as measurable, interconnected constructs.

Future research priorities drawn from Table 3 include

Establish consensus pipelines for IMU calibration and physiological preprocessing; Develop large-scale normative datasets for reaction-time and asymmetry metrics; Test lightweight neurophysiological add-ons (portable EEG/fNIRS) to bridge behavioral and kinematic domains; Quantify responsiveness (SRM/MDC) systematically across modalities.

Multidisciplinary perspective

Advancing dual-task-based ACL rehabilitation demands convergence of sport neuroscience, biomechanics, and clinical rehabilitation science. Neurophysiological constructs such as cortical inhibition efficiency can contextualize wearable-derived kinematic metrics, while biomechanical validation ensures measurement fidelity. Ultimately, progress depends less on new sensors than on shared psychometric standards and reproducible methods enabling individualized, data-driven RTS clearance.

Limitations and future directions

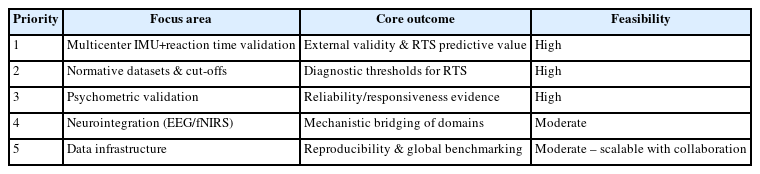

Despite consolidating 37 studies, this review remains constrained by the limited scale, cross-sectional design, and uneven psychometric reporting of the existing evidence. Most studies were single-center and short-term, and fewer than half quantified validity or reliability formally. To move from descriptive feasibility to standardized clinical implementation, a prioritized and feasible roadmap is required. The following five actions are ranked by urgency and feasibility within current resources. The summary of the priority roadmap is outlined in Table 4.

Large-scale multicenter validation: most urgent and highest impact

Rationale: Table 2, 3 show strong within-study validity for IMU+reaction-time dual-task frameworks (ICC ≈ 0.9, RMSE<5°), but these have only been demonstrated in isolated cohorts. Without multicenter replication, external validity and sport-specific generalizability remain unknown.

Objective: Conduct coordinated, multicenter studies using standardized Go/No-Go+IMU protocols to assess inter-site reproducibility and predictive validity for RTS outcomes.

Feasibility: Wearables are already field-ready (setup<20 min, battery ≈ 12 hr). Cloud-based data sharing and shared preprocessing pipelines make multicenter implementation technically achievable within current infrastructure.

Normative datasets and return-to-sport cut-off thresholds: high priority

Rationale: No study in Table 2, 3 established normative reference values for DTC %, reaction-time delay, or limb-symmetry index. Such benchmarks are essential to move from descriptive monitoring to diagnostic decision-making.

Objective: Aggregate multicenter data to derive age-, sex-, and sport-stratified norms, anchored to verified psychometric indices (ICC, SRM, MDC).

Feasibility: Highly achievable with current IMU and behavioral datasets; normative ranges could be generated within one to two collaborative study cycles.

Systematic psychometric validation of wearable-based measures: essential foundation

Rationale: Table 2, 3 report variable reliability (IMU ICC=0.85–0.98; behavioral ≈ 0.83–0.94) but inconsistent test–retest or MDC data. Without these, clinicians cannot distinguish true recovery from measurement noise.

Objective: Replicate IMU-MoCap concurrent validity, and determine responsiveness (SRM) and MDC for field protocols.

Feasibility: Requires repeated-session designs rather than new hardware; easily realizable within existing rehabilitation timelines.

Stepwise neurointegration (electroencephalography/functional near-infrared spectroscopy+inertial measurement unit): mid-term opportunity

Rationale: Physiological systems in Table 2 (EEG, fNIRS, TMS) revealed meaningful cortical activation patterns but lacked reproducibility. Integrating portable EEG/fNIRS with behavioral-kinematic data could bridge motor and neural control levels.

Feasibility: Currently limited by cost, setup time, and artifact control. Short-term use should remain pilot-scale, yet emerging compact EEG/fNIRS modules and automatic synchronization with IMU streams make broader integration plausible within 3–5 years.

Open data infrastructure and shared pipelines: mid-term but foundational

Rationale: Inconsistent filtering, sampling, and preprocessing pipelines were the dominant methodological barriers identified in Table 2, 3. Without common schemas, multicenter validation cannot produce comparable outputs.

Objective: Develop an open, standardized repository containing sensor metadata (task type, sampling rate, sensor placement) and harmonized preprocessing scripts.

Feasibility: Academia–industry collaborations can leverage existing open-source analytics; implementation is realistic within current technical ecosystems.

Overall synthesis

The most urgent need is multicenter replication of the validated IMU+reaction-time dual-task paradigm, immediately followed by the creation of normative datasets and psychometric reliability frameworks. Neurointegration and open-data infrastructure represent the next strategic phase, enabling mechanistic insight and cross-laboratory reproducibility. Advancing along this sequence will convert current heterogeneous dual-task studies into a standardized, evidence-anchored clinical system for ACL rehabilitation and RTS decision-making.

CONCLUSION

Cognitive–motor dual-task assessment marks a conceptual and methodological shift in ACL rehabilitation—from isolated biomechanical or strength evaluations to ecologically valid testing that mirrors the cognitive–motor demands of real-sport environments. Evidence synthesized from the 37 studies in Table 1, 2 demonstrates that when behavioral, kinematic, and physiological indices are combined, clinicians can detect residual neurocognitive-motor deficits that conventional single-task tests overlook.

Integrated evidence and clinical meaning

Behavioral reaction-time and accuracy metrics showed excellent reproducibility (ICC ≈ 0.83–0.94), while IMU-based kinematics achieved near-laboratory validity versus MoCap (ICC>0.9, RMSE<5°). These complementary domains—attention control and movement symmetry—form the most psychometrically mature foundation for clinical translation. Physiological measures (EEG, fNIRS, HRV) provided mechanistic insight but remain limited by preprocessing heterogeneity and insufficient test–retest data. Thus, dual-task assessment now offers a structured, evidence-anchored framework capable of quantifying how athletes allocate attention, inhibit actions, and coordinate movement under cognitive load.

Novel contribution

The novelty of this synthesis lies not in proposing new sensors, but in unifying validated task–device–metric combinations—such as Go/No-Go tasks coupled with IMU-derived asymmetry and reaction-time cost—into a standardized, psychometrically grounded template. By embedding validity, reliability, and responsiveness within each measurement domain, the review advances dual-task testing from experimental feasibility toward clinical actionability for RTS decisions. This transition reframes cognitive–motor assessment as an applied, data-driven component of individualized ACL rehabilitation.

Strategic priorities for continued development

Progress toward full clinical deployment depends on sequential, feasible steps grounded in the current evidence base:

1) Multicenter validation of the IMU+reaction-time framework (most urgent)

Large-scale trials across rehabilitation centers should verify reproducibility and external validity of standardized dual-task protocols.

2) Normative datasets and RTS cut-off thresholds (high priority)

Pooling multicenter data will enable creation of reference ranges and cut-offs for DTC and reaction-time delay, allowing objective RTS classification by age, sex, sport, and graft type.

3) Comprehensive psychometric validation (essential foundation)

Systematic evaluation of test–retest reliability, sensitivity to change, and MDC will distinguish true recovery from measurement noise.

Mid-term opportunities

Incremental neurointegration-linking portable EEG or fNIRS with behavioral-kinematic data—offers deeper insight into cortical mechanisms of motor control, though short-term feasibility remains limited by cost and setup demands. Parallel development of open, standardized data infrastructures for preprocessing, metadata exchange, and cloud-based sharing will enhance reproducibility, accelerate meta-analyses, and enable global benchmarking across laboratories.

Translational outlook

Wearable-enabled dual-task assessment now bridges the gap between high-precision laboratory systems and field-ready clinical applications. With continued standardization, multicenter collaboration, and psychometric rigor, dual-task testing is poised to become a cornerstone of personalized, evidence-based ACL rehabilitation, transforming cognitive–motor assessment from a research innovation into a clinically validated, globally scalable standard that improves both safety and effectiveness in modern sports medicine.

Notes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jun Woo KWON had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Author reviewed this manuscript and agreed to individual contributions.

Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation, writing–original draft, reviewing & editing: JWK.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No existing or potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data presented in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.