| Korean J Health Promot > Volume 25(1); 2025 > Article |

|

ABSTRACT

Background

Methods

Results

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Yu Ri CHOE ad full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors reviewed this manuscript and agreed to individual contributions.

Conceptualization: all authors. Data curation: MLK and JRJ. Formal analysis: JRJ and YRC. Investigation: MLK. Methodology: MLK and JRJ. Project administration: MLK and YRC. Software: JRJ and YRC. Supervision: YRC. Validation: YRC. Visualization: JRJ and YRC. WritingŌĆōoriginal draft: MLK. WritingŌĆōreview & editing: JRJ and YRC.

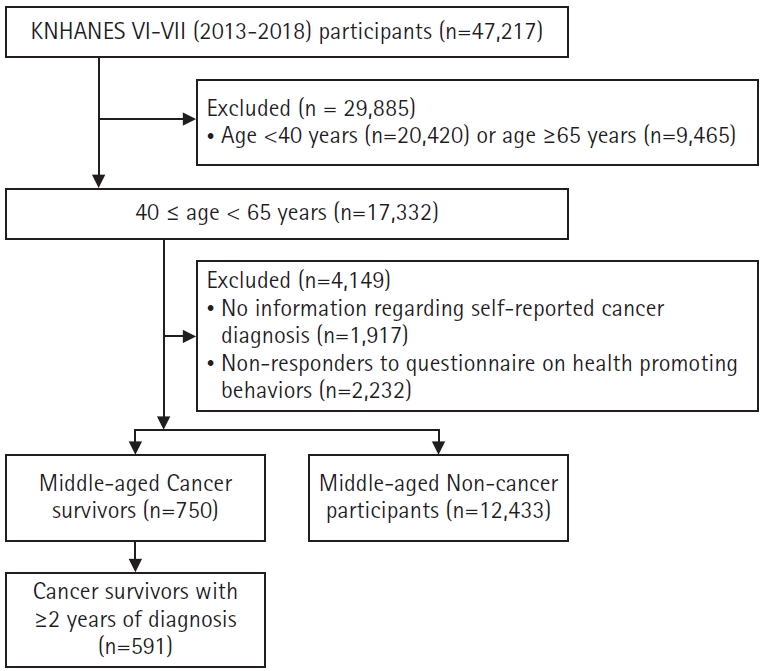

Fig.┬Ā1.

Table┬Ā1.

Table┬Ā2.

| Value | |

|---|---|

| Total | 591 |

| Single primary cancer | |

| ŌĆāThyroid | 152 (25.7) |

| ŌĆāBreast | 114 (19.3) |

| ŌĆāCervix | 78 (13.2) |

| ŌĆāStomach | 76 (12.9) |

| ŌĆāColon | 39 (6.6) |

| ŌĆāLung | 10 (1.7) |

| ŌĆāLiver | 10 (1.7) |

| ŌĆāOthersa | 95 (16.1) |

| Double primary cancer | 17 (2.9) |

| Years since diagnosis | |

| ŌĆā2ŌĆō5 | 201 (34.0) |

| ŌĆāŌēź5┬Ā | 390 (66.0) |

Table┬Ā3.

Table┬Ā4.

| Model 1a | Model 2b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Cancer screening (yes) | 1.22 (0.97ŌĆō1.53) | 0.089 | 1.22 (0.97ŌĆō1.53) | 0.092 |

| Alcohol consumption (yes) | 0.64 (0.51ŌĆō0.81) | <0.001 | 0.64 (0.52ŌĆō0.81) | <0.001 |

| Smoking (yes) | 0.64 (0.42ŌĆō0.97) | 0.034 | 0.65 (0.43ŌĆō0.99) | 0.043 |

| Physical activity (yes) | 1.33 (1.08ŌĆō1.63) | 0.008 | 1.33 (1.08ŌĆō1.64) | 0.008 |

| Sedentary time (Ōēź7 hr) | 1.15 (0.94ŌĆō1.40) | 0.175 | 1.15 (0.94ŌĆō1.40) | 0.176 |

| Dietary management (yes) | 1.47 (1.17ŌĆō1.83) | <0.001 | 1.47 (1.17ŌĆō1.84) | <0.001 |

aModel 1 was adjusted for PSM and significant covariates (P<0.1) identified via the univariate analyses of all health-related behaviors. For cancer screening adherence, significant covariates included sex, marital status, education level, household income level, comorbidities, activity limitations, and self-reported health status. For alcohol consumption, significant covariates included age, sex, BMI, education level, employment status, comorbidities, activity limitations, and self-reported health status. For smoking status, significant covariates included sex, BMI, marital status, employment status, household income level, residential area, activity limitations, stress level, and self-reported health status. For physical activity, significant covariates included age, marital status, education level, household income level, residential area, activity limitations, stress level, and self-reported health status. For sedentary behavior, significant covariates included age, sex, education level, household income level, stress level, and self-reported health status. For dietary management, significant covariates included sex, BMI, employment status, comorbidities, and activity limitations.

REFERENCES

-

METRICS

-

- 0 Crossref

- 0 Scopus

- 1,177 View

- 17 Download

- ORCID iDs

-

Mi Lee KIM

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0521-4561Ju Ri JEONG

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3544-2522Yu Ri CHOE

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4557-2323 - Related articles

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print