| Korean J Health Promot > Volume 19(3); 2019 > Article |

|

ABSTRACT

Background

Methods

Results

REFERENCES

Figure 1

The distribution of energy drink consumption frequency in boys and girls. Differences between boys and girls were significantly different (P<0.001), calculated by Rao-Scott chi-square test.

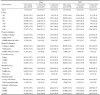

Table 2

General characteristics according to energy drink consumption in boys and girlsa

Values are presented as mean±standard error or number (%).

aDifferences between general characteristics and energy drink consumption in boys and girls were calculated by generalized linear model (GLM) for continuous variables and by Rao-Scott chi-square test for categorical variables, and all P values were less than 0.001, except for that of residential area in girls (P=0.001).

Table 3

Association between energy drink consumption and dietary- or lifestyle-related behavior in boys and girls

Values are presented as odds ratio and 95% confidence interval, calculated by multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Abbreviation: ref., reference.

aDependent variables: fruit intake ≥3 vs. <3 times/wk (ref.); vegetables intake ≥1 vs. <1 time/d (ref.); milk intake ≥5 vs. <5 times/wk (ref.); soda intake ≥3 vs. <3 times/wk (ref.); sweet-drink intake ≥3 vs. <3 times/wk (ref.); fast food intake ≥1 vs. <1 time/wk (ref.); skipping breakfast ≥3 vs. <3 days/wk (ref.); underweight vs. normal weight (ref.); overweight and obesity vs. normal weight (ref.); smoking yes vs. no (ref.); drinking yes vs. no (ref.); moderate exercise ≥5 vs. <5 times/wk (ref.); vigorous exercise ≥3 vs. <3 times/wk (ref.); and muscular exercise ≥3 vs. <3 times/wk (ref.).

bAdjusted for age, grade, academic achievement, paternal education, maternal education, economic status, residential area and residential type.

Table 4

Association between energy drink consumption and mental health-related behavior in boys and girls

Values are presented as odds ratio and 95% confidence interval, calculated by multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Abbreviation: ref., reference.

aDependent variables: sleep hours ≥8 vs. <8 hours/d (ref.); sleep quality satisfactory vs. non-satisfactory (ref.); excessive stress yes vs. no (ref.); sadness or depression yes vs. no (ref.); suicide ideation yes vs. no (ref.); perceived health yes vs. no (ref.); perceived happiness yes vs. no (ref.).

bAdjusted for age, grade, academic achievement, paternal education, maternal education, economic status, residential area and residential type.

-

METRICS

-

- 7 Crossref

- 0 Scopus

- 2,153 View

- 11 Download

- Related articles

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print