Energy Drink Consumption and Dietary-, Lifestyle-, and Mental Health-Related Behaviors in Korean Adolescents: Based on the 10th–13th Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-Based Survey

-

Jiwon Oh1

, Jayong Chung2

, Jayong Chung2

- Received September 09, 2019 Revised September 26, 2019 Accepted September 30, 2019

- ABSTRACT

-

- Background

- Energy drinks (EDs), functional beverages with high concentrations of caffeine, can cause health risks. This study examined the frequency of ED consumption and related factors in Korean adolescents.

- Methods

- Data from the 10th-13th Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey was used, and a total of 137,101 boys and 130,806 girls were included in the final analyses. Differences in ED consumption and associated factors were analyzed using the Rao-Scott chi-square test and a multivariate logistic regression analysis, reflecting of the complex sample design.

- Results

- In total, 17.3% boys and 12.9% girls consumed EDs more than once a week (P<0.001). In particular, 24.2% of all high-school students in the 12th grade consumed more than three EDs a week. After adjusting for confounding factors, a multivariate logistic regression analysis indicated that higher ED consumption was significantly associated with a higher soda, sweet-drink, and fast food intake; skipping breakfast; a lower vegetable intake; depression; suicidal thoughts; sleep deprivation; and increased smoking and alcohol drinking.

- Conclusions

- ED consumption is associated with undesirable dietary-, lifestyle-, and mental health-related behaviors, suggesting the need for appropriate nutrition education in adolescents.

- NOTES

- NOTES

This report was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government, NRF-2017R1A2B1009697.

- REFERENCES

- REFERENCES

- 1. Lee HS, Kwon SO, Yon M, Kim D, Lee JY, Nam J, et al. Dietary total sugar intake of Koreans: based on the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES), 2008-2011. J Nutr Health 2014;47(4):268-276.

[Article]2. Arria AM, Bugbee BA, Caldeira KM, Vincent KB. Evidence and knowledge gaps for the association between energy drink use and high-risk behaviors among adolescents and young adults. Nutr Rev 2014;72 Suppl 1:87-97.

[Article] [PubMed] [PMC]3. Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. Study of establishment of recommended daily allowance for caffeine. Cheongju: Ministry of Food and Drug Safety; 2007. p. 136-158.4. Yang YM, Huh W, Jeong E, Lee JJ, Choi EJ. An analysis of consumption patterns of high-caffeinated energy drinks and adverse effects by surveys from students at middle and high schools in Korea. Yakhak Hoeji 2014;58(6):387-396.5. James JE, Baldursdottir B, Johannsdottir KR, Valdimarsdottir HB, Sigfusdottir ID. Adolescent habitual caffeine consumption and hemodynamic reactivity during rest, psychosocial stress, and recovery. J Psychosom Res 2018;110:16-23.

[Article] [PubMed]6. Sanchis-Gomar F, Pareja-Galeano H, Cervellin G, Lippi G, Earnest CP. Energy drink overconsumption in adolescents: implications for arrhythmias and other cardiovascular events. Can J Cardiol 2015;31(5):572-575.

[Article] [PubMed]7. Harris JL, Munsell CR. Energy drinks and adolescents: what’s the harm? Nutr Rev 2015;73(4):247-257.

[Article] [PubMed]8. Ryu SH. Energy drink consumption status and associated factors among male and female high school students in Deajon area. Korean J Food Nutr 2016;29(6):899-910.

[Article]9. Park EJ, Kim SY. Caffeinated food consumption patterns and level among high school students in Yongin region. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr 2017;46(9):1128-1136.10. Park SH, Lee SH, Chang KJ. Intake-related factors and educational needs regarding energy drinks in female high school students in the Incheon area. J Nutr Health 2017;50(5):460-471.

[Article]11. Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Korea youth risk behavior web-based survey [Internet]. Sejong: Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2019;Accessed Jun 5, 2019]. Available from: https://www.cdc.go.kr/yhs/home.jsp?id=m03_0512. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2017 Korean national growth chart [Internet]. Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017;Accessed Jun 12, 2019]. Available from: https://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/knhanes/sub08/sub08_01.do13. Yoo HS, Sim KH. Survey on the high-caffeine energy drink consumption status of university students in Seoul. J East Asian Soc Diet Life 2014;24(3):407-420.

[Article]14. Kim TY, Kim SM, Kim JY, Im JY, Yu H, Han YH, et al. Awareness and consumption of energy drinks and associated factors among college students in Cheongju. Korean J Community Nutr 2018;23(1):60-72.

[Article]15. Jin MJ, Yoon CH, Ko HJ, Kim HM, Kim AS, Moon HN, et al. The relationship of caffeine intake with depression, anxiety, stress, and sleep in Korean adolescents. Korean J Fam Med 2016;37(2):111-116.

[Article] [PubMed] [PMC]16. National Institute of Food and Drug Safety Evaluation. Sugar database compilation for commonly consumed foods. Cheongju: National Institute of Food and Drug Safety Evaluation; 2015. p. 226-236.17. Bernabé E, Vehkalahti MM, Sheiham A, Aromaa A, Suominen AL. Sugar-sweetened beverage and dental caries in adult: a 4-year prospective study. J Dent 2014;42(8):952-958.

[PubMed]18. Richelsen B. Sugar-sweetened beverages and cardio-metabolic disease risks. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2013;16(4):478-484.

[Article] [PubMed]19. Lien L, Lien N, Heyerdahl S, Thoresen M, Bjertness E. Consumption of soft drinks and hyperactivity, mental distress, and conduct problems among adolescents in Oslo, Norway. Am J Public Health 2006;96(10):1815-1820.

[Article] [PubMed] [PMC]20. World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Technical Report Series 916: Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic disease. Geneva: WHO; 2013. p. 57-60.21. Keast RS, Swinburn BA, Sayompark D, Whitelock S, Riddell LJ. Caffeine increases sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in a free-living population: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Nutr 2015;113(2):366-371.

[Article] [PubMed] [PMC]22. Libuda L, Alexy U, Buyken AE, Sichert-Hellert W, Stehle P, Kersting M. Consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and its association with nutrient intakes and diet quality in German children and adolescents. Br J Nutr 2009;101(10):1549-1557.

[Article] [PubMed]23. Lim YK. The effects of caffeinated beverage intake on serum iron(Fe) and total iron binding capacity(TIBC). Korean Association of Addiction Crime Review 2017;7(1):93-112.24. Lim SA, Rho SN. Micro mineral responses to caffeine in serum and urine of healthy young females. Korean J Nutr 1993;26(9):1118-1128.25. Hong KJ, Lee JW, Park MS, Cho YS. A study on the promotion of adolescents milk consumption (I): milk preference and intake pattern of urban adolescents. J Korean Diet Assoc 2007;13(1):61-72.26. Utter J, Denny S, Teevale T, Sheridan J. Energy drink consumption among New Zealand adolescents: association with mental health, health risk behaviours and body size. J Paediatr Child Health 2018;54(3):279-283.

[PubMed]27. Korea Consumer Agency. Survey on Safety of Energy Drink. Eumseong: The Consumer Safety Center; 2013. p. 61-63.28. An SM, Park JS, Kim SH. Effect of energy drink dose on exercise capacity, heart rate recovery and heart rate variability after high-intensity exercise. J Exerc Nutrition Biochem 2014;18(1):31-39.

[Article] [PubMed] [PMC]29. Aepli A, Kurth S, Tesler N, Jenni OG, Huber R. Caffeine consuming children and adolescents show altered sleep behavior and deep sleep. Brain Sci 2015;5(4):441-455.

[Article] [PubMed] [PMC]30. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Suicide rates [Internet]. Paris: OECD; 2017;Accessed Sep 8, 2019]. Available from: https://data.oecd.org/healthstat/suicide-rates.htm

Figure 1

Table 2

Values are presented as mean±standard error or number (%).

aDifferences between general characteristics and energy drink consumption in boys and girls were calculated by generalized linear model (GLM) for continuous variables and by Rao-Scott chi-square test for categorical variables, and all P values were less than 0.001, except for that of residential area in girls (P=0.001).

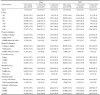

Table 3

Values are presented as odds ratio and 95% confidence interval, calculated by multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Abbreviation: ref., reference.

aDependent variables: fruit intake ≥3 vs. <3 times/wk (ref.); vegetables intake ≥1 vs. <1 time/d (ref.); milk intake ≥5 vs. <5 times/wk (ref.); soda intake ≥3 vs. <3 times/wk (ref.); sweet-drink intake ≥3 vs. <3 times/wk (ref.); fast food intake ≥1 vs. <1 time/wk (ref.); skipping breakfast ≥3 vs. <3 days/wk (ref.); underweight vs. normal weight (ref.); overweight and obesity vs. normal weight (ref.); smoking yes vs. no (ref.); drinking yes vs. no (ref.); moderate exercise ≥5 vs. <5 times/wk (ref.); vigorous exercise ≥3 vs. <3 times/wk (ref.); and muscular exercise ≥3 vs. <3 times/wk (ref.).

bAdjusted for age, grade, academic achievement, paternal education, maternal education, economic status, residential area and residential type.

Table 4

Values are presented as odds ratio and 95% confidence interval, calculated by multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Abbreviation: ref., reference.

aDependent variables: sleep hours ≥8 vs. <8 hours/d (ref.); sleep quality satisfactory vs. non-satisfactory (ref.); excessive stress yes vs. no (ref.); sadness or depression yes vs. no (ref.); suicide ideation yes vs. no (ref.); perceived health yes vs. no (ref.); perceived happiness yes vs. no (ref.).

bAdjusted for age, grade, academic achievement, paternal education, maternal education, economic status, residential area and residential type.