Associations between Fear of Cancer Recurrence and Health-Related Quality of Life, Psychological Distress, and Health Behaviors in Cancer Survivors

Article information

Abstract

Background

Fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) is a prevalent psychological concern among cancer survivors, closely linked to diminished health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and increased psychological distress. However, its impact on health-related behaviors remains poorly understood. This study investigated associations between FCR, HRQoL, psychological distress, and health-related behaviors in a diverse cancer survivor population.

Methods

This cross-sectional study analyzed data from 326 adult cancer survivors across diverse cancer types. FCR was assessed using four items addressing concern about recurrence, metastasis, second cancer, and follow-up and participants were classified as high FCR. HRQoL was evaluated using the EuroQol 5-Dimension Questionnaire (EQ-5D), EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS), and European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30); psychological symptoms were measured by the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7). Health-related behaviors included recent screening, vaccination, and physical activity. Linear regression was used for continuous outcomes and logistic regression for binary outcomes, controlling for demographic and clinical covariates.

Results

Participants with high FCR demonstrated significantly poorer HRQoL across multiple domains, including Global Health Status/Quality of Life (β=–10.56, 95% confidence interval [95% CI]: –14.82 to –6.29, P<0.001), physical functioning (β=–7.04, P<0.001), and emotional functioning (β=–12.86, P<0.001). They also reported greater fatigue (β=11.11, P<0.001), pain (β=9.85, P<0.001), and financial difficulty (β=17.32, P<0.001). High FCR was strongly associated with depressive (PHQ-9: β=3.10, P<0.001) and anxiety symptoms (GAD-7: β=2.70, P<0.001). In contrast, no significant associations were found between FCR and health-related behaviors.

Conclusions

High FCR is strongly associated with impaired HRQoL and increased psychological distress but does not translate into increased engagement in preventive health behaviors. These findings underscore the need for integrated interventions addressing both emotional and behavioral aspects of survivorship care.

INTRODUCTION

Advancements in cancer diagnosis and treatment, the expansion of national screening programs, and growing public awareness have led to a steady increase in the number of cancer survivors in Korea. As of 2020, approximately 2.56 million individuals in Korea had survived cancer, comprising nearly 5% of the national population, with the proportion of five-year survivors rising from 38.7% in 2010 to 57.7% in 2020 [1]. These trends signal a paradigm shift in the conceptualization of cancer—from an acute illness to a chronic condition requiring long-term survivorship care.

Even after completing primary treatment, many cancer survivors continue to face a variety of physical, psychological, and social challenges. Among these, fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) has emerged as one of the most common and persistent concerns [2-4]. FCR ranges from mild anxiety to clinically significant distress, with its intensity varying by cancer type, time since diagnosis, sex, and psychosocial characteristics. Excessive FCR has been linked to depression, anxiety, insomnia, and overall declines in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [4,5].

FCR may also influence survivors’ health behaviors, although the direction and magnitude of its effects remain unclear. For instance, a study of young breast cancer survivors revealed that individuals with high FCR were more likely to undergo screening but also engaged in detrimental behaviors such as smoking and alcohol use [6]. Other findings suggest that FCR can heighten somatic symptom sensitivity and psychological stress, influencing health behaviors and lifestyle management [7]. In colorectal cancer survivors, FCR has been associated with engagement in preventive behaviors like physical activity and smoking cessation [8]. Nevertheless, many prior studies have focused on narrow populations, limiting their generalizability. Moreover, some evidence indicates that while FCR significantly affects psychological functioning and HRQoL, its influence on health-related behaviors may be modest [9].

Accordingly, this study utilized data from the pilot phase of the Korean Nationwide Survey for Cancer Survivorship, the first population-based investigation of FCR in Korean survivors. By including six major cancer types (stomach, colorectal, liver, breast, cervical, and lung), the findings are more generalizable than those of cancer-specific studies. FCR was measured using a multidimensional tool covering recurrence, metastasis, secondary cancer, and follow-up concerns. This study assessed the associations between HRQoL, psychological symptoms, and health behaviors, addressing the limitations of prior research focused on narrower populations or outcomes. These findings inform integrated survivorship care that considers both emotional and behavioral aspects.

METHODS

Study design and participants

This study used data derived from a pilot survey conducted prior to the Korean Nationwide Survey for Cancer Survivorship. The pilot survey aimed to evaluate the feasibility of the study protocol, refine the questionnaire, and validate the data collection procedures. The survey covered a wide range of topics, including treatment history, current health status, quality of life, unmet needs, health behaviors, health policy indicators, and sociodemographic characteristics.

The eligibility criteria for the study participants were as follows: adults aged ≥19 years who were diagnosed with one of the six major cancers in Korea (stomach, colorectal, liver, breast, cervical, or lung cancer) and had survived for at least 1 year post-diagnosis. Participants were required to have completed primary cancer treatment, such as surgery, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy. Exceptions were made for individuals who were currently receiving oral chemotherapy without evidence of disease progression, who received adjuvant hormonal therapy following breast cancer treatment, or who exhibited no disease progression after receiving local treatment for liver cancer. Individuals currently undergoing treatment for recurrent or metastatic cancer and those diagnosed with terminal stage cancer were excluded.

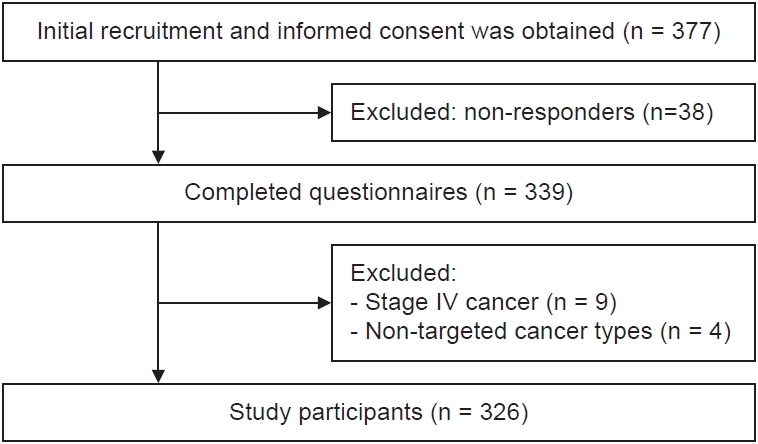

Recruitment was conducted in collaboration with the medical staff at four institutions in Korea—namely, a national cancer center, two major private hospitals, and a regional cancer center. A total of 377 participants were enrolled from 6 November 2023 to 29 March 2024. Data were collected by a professional survey agency via either in-person interviews or self-administered online questionnaires, based on participant preferences. Out of 377 recruited individuals, 339 completed the survey. After excluding nine participants with stage IV cancer and four individuals diagnosed with non-major cancers (e.g., thyroid cancer, carcinoid sarcoma), 326 participants were finally included in the analysis (Fig. 1).

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital (IRB no. CNUHH-2025-073). Informed consent was obtained through face-to-face interviews with trained research nurses using a web-based form.

Covariates

Sociodemographic variables included age, sex, marital status, educational level, monthly household income, comorbidities, and employment status. Marital status was dichotomized into “single (including divorced or widowed)” and “married or cohabiting.” Educational level was categorized into three groups: middle school graduate or lower, high school graduate, and college graduate or higher. Monthly household income was divided into quartiles. Comorbidity status was assessed based on the presence of major chronic conditions and categorized into “none” and “one or more.” Employment status was classified according to current economic activity as either “employed” or “unemployed.”

Cancer-related clinical variables included cancer type, stage, treatment history, and time since diagnosis. Cancer types were classified as breast, stomach, colorectal, lung, cervical or uterine, and liver. Cancer stage was categorized as stage 0, I, II, or III or unknown. Treatment history included surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, hormone therapy, and other procedures, each treated as a separate binary variable. Time since diagnosis was categorized into “1.0 to <4.5 years” and “4.5 to ≤10 years.”

FCR was assessed using four items that evaluated concerns regarding regular medical check-ups, the development of a second primary cancer, cancer recurrence, and metastasis. Each item was rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“not at all”) to 4 (“very much”). To classify the level of FCR, the number of items rated as 3 (“quite”) or 4 (“very much”) was counted. Participants who endorsed a score of 3 or higher on two or more items were categorized as having high FCR, whereas those with fewer than two such responses were classified as having low FCR. This classification reflects a multidimensional approach to capturing clinically meaningful levels of recurrence-related fear across multiple domains [10,11].

Health-related quality of life and psychological distress

HRQoL was assessed using the EuroQol 5-Dimension Questionnaire (EQ-5D), EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS), and European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30, version 3.0).

The EQ-5D [12] assesses five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression), each rated on a 3-point scale. For analysis, responses were dichotomized: “no problems” (score=1) coded as 0, and “some” or “extreme problems” (scores=2 or 3) coded as 1. The EQ-VAS [12] is a 20-cm vertical scale ranging from 0 (worst health) to 100 (best health), reflecting self-rated current health. The EORTC QLQ-C30 [13] is a 30-item questionnaire developed to measure HRQoL in patients with cancer. It comprises the three components: the five functional scales, the nine symptom scales, and a Global Health Status/Quality of Life (GHS/QoL) scale. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale (“not at all” to “very much”) or a 7-point scale for GHS/QoL items. All scores were linearly transformed to a 0–100 scale, with higher scores indicating better functioning on the functional and GHS/QoL scales or worse symptoms on the symptom scales. The Korean version shows good reliability (Cronbach’s α>0.70 for most subscales; α=0.60 for cognitive function) [14].

Depression was measured using the Korean version of the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) [15], with scores ranging from 0 to 27 and higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. The Korean version has high internal consistency (α=0.88) [16]. Anxiety was assessed via the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7) [17], with scores ranging from 0 to 21, also showing excellent reliability in Korean validation studies (α=0.91) [18].

Health-related behaviors

Health-related behaviors were assessed via self-administered questionnaires and categorized as change-or status-based.

Change-based behaviors included weight control, alcohol consumption, and smoking. Weight-control efforts were assessed using self-reported efforts to reduce, maintain, or gain weight over the past year. Alcohol consumption and smoking behaviors were categorized as no change, reduction, cessation after diagnosis, or lifelong abstinence. Status-based behaviors included recent health check-ups (within 2 years), cancer screening (for cancers other than the index cancer), vaccinations (pneumococcal, herpes zoster, and seasonal influenza), physical activity, use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), and nutritional supplements.

Physical activity was assessed by the number of days per week participants walked ≥10 minutes and did strength training (e.g., push-ups, sit-ups, weightlifting) over the past week, categorized as <5 or ≥5 days for walking and <2 or ≥2 days for strength training [19] CAM use was assessed as ever or never used for cancer treatment after the diagnosis. The current use of nutritional supplements, including vitamins and traditional remedies, was also recorded.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics are summarized as means with standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies with percentages for categorical variables. Group comparisons based on FCR were performed using independent t-tests and chi-square tests.

To assess association between FCR and HRQoL or psychological symptoms, multivariate linear and logistic regression models were used for continuous and binary outcomes, respectively. All models were adjusted for age, sex, cancer type, cancer stage, comorbidities, time since cancer diagnosis, educational level, monthly household income, and employment status. Multicollinearity was assessed using variance inflation factors; all were <1.45. Bonferroni correction was applied for multiple comparisons with a significance threshold of P<0.0024.

Associations between FCR and health-related behaviors were examined using the chi-squared test. Multivariable logistic regression analyses assessed independent associations between each behavior and high FCR (coded 1), adjusting for demographic and clinical covariates. Each behavior was entered as the main independent variable in a separate model, and statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

All analyses were conducted using Python version 3.11.4 (Python Software Foundation) [20], with the statsmodels (v0.14.0) [21], pandas (v2.0.3) [22], and scikit-learn (v1.3.0) [23] libraries.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the participants

A total of 326 cancer survivors were included in the analysis (Table 1), of whom 149 (45.7%) were classified as having high FCR and 177 (54.3%) as having low FCR. The mean age of participants was 57.5±10.7 years, with the high FCR group being younger than the low FCR group (56.3±10.2 years vs. 58.5±11.0 years). Female accounted for 69.9% of the total sample and were slightly more represented in the high FCR group (71.1% vs. 68.9%). The majority of participants were married or cohabiting (73.6%) and had attained a college-level education or higher (55.2%). The distribution of monthly household income was relatively even across quartiles. Comorbid conditions were present in 30.1% of participants, and 56.1% were employed at the time of the survey. Breast cancer was the most common cancer type (32.2%), followed by stomach (23.0%) and colorectal cancer (15.0%). Most participants had been diagnosed with early-stage disease (stage 0–II, 71.8%). Nearly all participants had undergone surgery (94.5%), and over half had received chemotherapy (49.4%) or radiotherapy (39.6%). Time since diagnosis ranged from 1.0 to 10 years, with 53.4% having been diagnosed within the past 4.5 years. The mean total FCR score was 9.9±3.3.

There were no statistically significant differences in sociodemographic or clinical characteristics between the low and high FCR groups (all P>0.05), except for cancer type (P=0.005). Specifically, breast cancer was more prevalent among participants with high FCR (43.6% vs. 22.6%), while colorectal cancer was more common in the low FCR group (27.1% vs. 18.1%). The distributions of other cancer types showed no clear differences between groups.

Health-related quality of life and psychological symptoms according to fear of cancer recurrence

Table 2 presents the comparisons of HRQoL and psychological symptoms between participants with low and high FCR. After adjusting for age, sex, cancer type, cancer stage, comorbidity, time since diagnosis, education level, household income, employment status, and study group, several significant differences were observed across multiple domains.

On the EQ-5D, participants in the high FCR group were more likely to report problems in pain/discomfort (odds ratio [OR]=2.31, 95% confidence interval [95% CI]: 1.44–3.71; P<0.001), and anxiety/depression (OR=4.26, 95% CI: 2.58–7.02; P<0.001). The EQ-VAS score was also significantly lower in the high FCR group (β=–8.66, 95% CI: –12.55 to –4.77; P<0.001).

In the EORTC QLQ-C30 domains, the high FCR group reported significantly lower scores in all functional scales, including physical (β=–7.04; P<0.001), role (β=–9.16; P<0.001), emotional (β=–12.86; P<0.001), cognitive (β=–9.82; P<0.001), and social functioning (β=–13.41; P<0.001), as well as in GHS/QoL (β=–10.56; P<0.001). Regarding symptom burden, participants with high FCR had significantly higher levels of fatigue (β=11.11; P<0.001), pain (β=9.85; P<0.001), insomnia (β=14.51; P<0.001), and financial difficulties (β=17.32; P<0.001). Although nausea/vomiting and appetite loss were more prevalent in the high FCR group (P=0.036 and P=0.023, respectively), they did not meet the Bonferroni-adjusted significance threshold (P<0.0024).

Psychological symptoms were also markedly elevated among participants with high FCR. Both PHQ-9 (β=3.10, 95% CI: 1.99–4.22; P<0.001) and GAD-7 scores (β=2.70, 95% CI: 1.89–3.52; P<0.001) were significantly higher compared to the low FCR group.

Health-related behaviors according to fear of cancer recurrence

Table 3 presents both the unadjusted prevalence of health-related behaviors in the low- and high-FCR groups and the adjusted associations derived from multivariable logistic regression. In chi-square analyses, no statistically significant differences were observed between groups for any change-based or status-based behavior. After adjusting for age, sex, cancer type, cancer stage, comorbidity, time since diagnosis, educational level, household income, and employment status, none of the health-related behaviors remained significantly associated with high FCR. For example, the adjusted OR for general health check-up was 0.97 (95% CI: 0.61–1.56; P=0.902), for cancer screening 1.21 (95% CI: 0.76–1.91; P=0.418), and for CAM use 0.97 (95% CI: 0.55–1.71; P=0.907).

DISCUSSION

This study examined how FCR is associated with HRQoL, psychological symptoms, and health-related behaviors among cancer survivors. While high FCR was clearly associated with greater psychological distress and significantly poorer HRQoL across multiple domains, it did not correspond to increased engagement in health behaviors such as screening, physical activity, or vaccination. These findings suggest a divergence between emotional burden and behavioral response, underscoring the need for integrated survivorship strategies that address both psychosocial and behavioral dimensions.

Consistent with the present study, prior research has shown that high FCR are significantly associated with diminished HRQoL and heightened psychological distress. Previous study of colorectal cancer survivors reported that higher FCR levels were correlated with lower functional scores on the EORTC QLQ-C30 and increased symptoms of anxiety and depression [24]. Similarly, research involving Korean stomach cancer survivor populations has indicated that FCR in stomach cancer survivors was associated with social, psychological, and HRQoL factors [5]. Consistent findings have also been observed among patients with advanced cancer, wherein high FCR was associated with substantial psychosocial burden [25]. The present study aligns with this body of evidence, revealing that individuals with high FCR exhibited significantly poorer scores across all functional domains of HRQoL—including physical, role, emotional, cognitive, and social functioning—as well as higher levels of symptom burden, particularly in relation to fatigue, insomnia, pain, and financial difficulties.

In contrast to symptoms such as fatigue, pain, insomnia, and financial difficulties, gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms—including nausea/vomiting, appetite loss, dyspnea, constipation, and diarrhea—demonstrated no statistically significant association with FCR (P>0.0023). GI symptoms are often perceived as non‑specific or treatment-related sequela rather than indicators of recurrence, particularly among non-GI cancers [5,24]. Moreover, FCR is fundamentally a cognitive‑emotional construct centered on the concern that cancer may return; it is more tightly tied to psychological distress and diminished functional domains than to isolated somatic complaints [3,4]. These findings are consistent with emerging evidence indicating that FCR correlates more strongly with fatigue, pain, and anxiety than with GI symptoms. Such a discrepancy emphasizes the need to consider both the interpretation and perceived salience of symptoms in understanding the psychological correlates of FCR.

Notably, multiple measures assessing psychological symptoms were included in this study, namely the EQ-5D anxiety/depression item, PHQ-9, and GAD-7. While each assesses facets of psychological well-being, they differ in both conceptual scope and psychometric design. The EQ-5D offers a singular, general indicator of emotional status within the broader context of HRQoL, whereas the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 are standardized multi-item instruments specifically developed to evaluate the severity of depressive and anxiety symptoms, respectively. The concurrent use of these measures permits a complementary assessment of emotional functioning, capturing both general distress and disorder-specific symptomatology.

Given that high FCR was not associated with increased engagement in screening, vaccination, weight control, alcohol use, smoking, physical activity, or supplement intake, several interpretative considerations warrant discussion. Contrary to the “teachable moment” hypothesis, which posits cancer experience and related fear motivate preventive action, findings suggest emotional distress alone may be insufficient to drive behavioral change [26,27]. This highlights the need for interventions combining psychosocial support with structured behavior-change strategies, rather than relying solely on psychological or educational approaches [28,29]. The conceptual distinction between psychological distress and behavioral adherence underscores the value of integrated multidisciplinary survivorship care that addresses both domains. CAM use and supplement intake were not evidence-based behaviors, but reflected broader coping responses to FCR. Although not medically validated, these behaviors may reflect emotionally driven adaptations offering insight into how cancer fear manifests behaviorally [30-32]. Moreover, recent evidence suggests FCR may indirectly affect behavior through unmet supportive care needs linked to lower screening participation, emphasizing the importance of addressing structural and psychosocial barriers alongside distress [9]. Finally, longitudinal research is needed to clarify how changes in FCR relate to health behaviors and whether individuals with persistently high FCR respond better to tailored interventions, providing more nuanced survivorship strategies [33,34].

In this study, FCR was not associated with cancer stage or time since diagnosis. While this may partly reflect limited variability, stage IV cases were excluded, and over half the participants were long-term survivors, possibly due to analytical constraints, as the time since diagnosis was dichotomized at 4.5 years. However, previous studies have reported high FCR in early stage [35,36] and long-term survivors [37,38], suggesting FCR is not solely determined by clinical status or time. It reflects the complex interplay of clinical and psychosocial factors, including cancer type, treatment history, and perceived support. Longitudinal studies are needed to clarify these associations with long-term survival, suggesting clinical indicators alone may be insufficient.

This study has several limitations. First, its cross-sectional design limits causal inferences. Although high FCR was associated with poor HRQoL and psychological distress, reverse causality is plausible; emotional distress may heighten FCR rather than result from it. Similarly, the null association with preventive behaviors should be interpreted cautiously, as distress may hinder engagement. These limitations highlight the need for longitudinal studies to clarify the directionality. Second, most variables were assessed via self-reports, potentially introducing recall and reporting biases. Social desirability may have influenced responses on psychological symptoms and health behaviors, possibly affecting the associations. Third, as a pilot study, the sample was relatively small, which may limit statistical power and generalizability. Fourth, FCR was assessed with four items on follow-up, secondary cancer, recurrence, and metastasis. High FCR was defined as a score ≥3 on at least two items, based on prior studies [39-41]. This approach balances clinical relevance and brevity, capturing key domains of recurrence-related fear while reducing respondent burden. Although not externally validated, it was deemed appropriate for a pilot study with a moderate sample size. Further refinement and psychometric validation are planned from an upcoming nationwide survivor survey. Fifth, inconsistent timeframes in assessing health-related behaviors may have affected the interpretation. Some behaviors (e.g., smoking, alcohol use, and weight control) were measured as post-diagnosis changes, whereas others (e.g., vaccination, physical activity, CAM use, and supplement intake) reflected current status. This heterogeneity complicates whether FCR affects initiation or maintenance of behaviors. Null findings should be interpreted cautiously; future studies should adopt standardized timeframes or longitudinal designs for clarification.

Despite these limitations, this study had several strengths. It provides an integrated perspective on the relationships between FCR, HRQoL, psychological distress, and health-related behaviors in a diverse cohort of cancer survivors. Findings showed high FCR was strongly associated with poorer HRQoL and greater psychological burden, yet did not lead to increased participation in health-promoting behaviors, such as screening, vaccination, or physical activity. This discrepancy challenges the assumption that emotional distress—particularly fear—naturally motivates positive behavioral changes. Clinically, the results underscore the need for multidisciplinary survivorship programs addressing psychological and behavioral dimensions rather than relying on FCR alone as a driver of health behavior. Tailored interventions integrating emotional support with structured behavioral-change strategies may be essential for promoting long-term health among cancer survivors.

Notes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Yu Ri CHOE full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors reviewed this manuscript and agreed to individual contributions.

Conceptualization: all authors. Data curation: YK and YRC. Formal analysis: SHC and YRC. Investigation: SHC. Methodology: YK and YRC. Project administration: YK and YRC. Software: SHC and YRC. Supervision: YRC. Validation: YK and YRC. Visualization: SHC and YRC. Writing–original draft: SHC. Writing–review & editing: SHC and YRC.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No existing or potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

FUNDING

This study was funded by a grant from the National Cancer Center of the Republic of Korea (NCC-2311470).

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data presented in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.