Met Care Needs for Living and Life Satisfaction among Disabled Older People in the Community: Secondary Data Analysis Using the Disability Life Dynamic Panel Survey

Article information

Abstract

Background

This study aimed to identify factors influencing life satisfaction with a focus on met or unmet care needs for living in older adults with disabilities.

Methods

This study analyzed the data of 2,220 disabled older people, using the fourth wave of the Disability Life Dynamic Panel Survey from the Korea Disables people’s Development Institute. We used descriptive statistics, t-tests, ANOVA, Pearson’s correlation coefficient, and multiple regression for our analyses.

Results

Social factors, employment status, and levels of depression influenced the life satisfaction of disabled older adults. Various social factors, including meeting social/leisure activity care need, having a higher number of close people, more frequent meetings with them, and engaging in social activities, significantly influenced better life satisfaction. This regression model explained 26% of the variance in life satisfaction.

Conclusions

This study highlights the influence of social factors, particularly the addressed social participation care needs, on the life satisfaction of older people with disabilities. Therefore, enhancing social networks and community-based programs is essential to help individuals sustain their social connections. Additionally, providing care to those who face challenges in participating will enable their ongoing engagement in social activities.

INTRODUCTION

As society ages, the prevalence of older adults with disabilities is steadily increasing. The Disability Survey by the Ministry of Health and Welfare indicated that those aged 65 and older represent 54.3% of the disabled population. This represents the highest percentage among all age groups with disabilities. This signifies an increase from 49.9% in 2020, underscoring the tendency to age within the disabled demographic [1]. Advanced age is associated with negative changes in physical, mental, and social functions, frequently resulting in a decline in quality of life and overall life satisfaction [2]. Older people with disabilities encounter compounded obstacles stemming from both age-related and disability-related issues, making them more vulnerable and requiring more social care [3].

A complex interaction of physical, social, and emotional factors influences life satisfaction in older adults. Previous studies have shown that various elements, such as social support, depression, physical health, and the ability to engage in activities of daily living (ADL), greatly influence life satisfaction in older adults [4]. Among these, ADL [5] and social relationships [4,6] are two of the most important for life satisfaction.

The deterioration of daily living abilities in older adults increases dependency on others, which negatively influences both physical function and social connections. This frequently results in social isolation, depression, and a subsequent decline in quality of life [7]. Older people with disabilities encounter substantial and prolonged limitations in performing daily living [8]. Over 30% of individuals with disabilities reportedly require assistance with daily living, and over 40% consider their support insufficient [9]. As a result, older individuals with disabilities are more prone to reduced life satisfaction, underscoring the need for specific interventions.

Social factors are another critical determinant of life satisfaction in later life [4,6]. As individuals age, their social networks typically diminish [10]. Older individuals with disabilities face several challenges, including physical limitations, social isolation, depression, and other difficulties [11,12]. Such challenges have a particularly adverse influence on their life satisfaction. The findings indicate that supporting care needs for living and fostering social relationships play crucial roles in improving life satisfaction among older individuals with disabilities. While these factors are essential for promoting independent living and preserving physical and emotional well-being, research on the relationship between care needs for living and life satisfaction in older individuals with disabilities remains insufficient. Therefore, this study aims to identify whether the care needs for living are met in older individuals with disabilities (Aim 1) and to identify the factors influencing their life satisfaction, with a particular focus on met or unmet care needs for living (Aim 2).

METHODS

Study design

This study is a secondary analysis using the 4th wave of Disability Life Dynamic Panel Survey [13] to investigate the factors influencing life satisfaction, with a focus on met or unmet care needs for living for older individuals with disabilities.

Data and ethical considerations

The Korea Disabled People’s Development Institute has performed the Disability Life Dynamic Panel Survey annually since 2018. It involves individuals who registered their disabilities with the Ministry of Health and Welfare from 2015 to 2017, along with their household members. Trained investigators conducted one-on-one, face-to-face interviews. In 2018, a panel of 6,121 participants was chosen to complete the first wave of the survey. Data can be acquired by submitting a request via the Disability Statistics Data Portal.

The participants in this study were 2,220 older adults aged 60 years and above who participated in the 4th survey conducted in 2021. This analysis included data that had no missing values for the key variables. This study was conducted with the approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the Gachon University (IRB No. 1044396-202410-HR-182-01).

Measurements

Life satisfaction

The overall life satisfaction was measured using a question with a 10-point Likert scale, ranging from “very dissatisfied=1” to “very satisfied=10.”

Influencing factors

Met care needs for living were assessed as follows.

The presence of a caregiver was assessed using a question asking, “Who assists with your living?” In this study, we classified those who answered “none” as “no caregiver,” while those who selected a spouse, parents, child, or others as “has caregiver.”

Met care needs for living were measured using questions about the degree of care needs required and the actual level of care received in living activities (such as washing and personal hygiene, mobility, eating, dressing, healthcare, and social/leisure activity participation). The degree of assistance required was measured with the question, “Please indicate the types and levels of living activities where you need assistance,” using a 4-point Likert scale from “no assistance needed=1” to “completely need assistance=4.” The degree of actual assistance received was measured with the question, “What areas do you mainly receive help with?” using a Likert scale from “no assistance received=1” to “completely assisted=4.” This study reclassified the items of washing and personal hygiene, mobility, eating, and dressing as ADL.

Met care needs for living were created by calculating the difference between the two questions (the degree of care needs required and the actual level of care received), categorizing as either “met” or “unmet.” If the difference between the two questions was 0 or less, it was classified as “met,” and if the difference was greater than 0, it was classified as “unmet.” For ADL, if any of the four sub-items were unmet, it was classified as “unmet.”

General characteristics include demographic and social factors. Demographic factors were measured using variables such as age, gender, education level, severity of disability, employment status, and depression. Depression was assessed using the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale-11. This scale consists of 11 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale from “rarely or none=1” to “most or all of the time=4.” The total score is calculated by summing the responses to the 11 items, with higher scores indicating greater levels of depression [14]. Social factors were measured by the number of close people, frequency of meetings, and participation in social activities. The number of close people was assessed by asking the question: “How many close friends, neighbors, and acquaintances do you have (people you can talk about personal concerns, family issues, and other matters)?” The frequency of meetings was measured with the question: “How often do you meet the friends, neighbors, and acquaintances mentioned above?” Participation in social activities was determined based on responses to questions about participation in activities such as religious activities, social gatherings, leisure activities, volunteer work, or political/organizational activities at least once a month. If the respondent answered “yes” to any of these activities, they were classified as “participation”; otherwise, they were classified as “no participation.”

Data analysis

The general characteristics and status of care needs for living were analyzed using descriptive statistics. The characteristics of life satisfaction by general characteristics were identified using t-test and ANOVA. The relationships between depression, the number of close people, and life satisfaction were analyzed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Multiple regression was used to identify factors influencing life satisfaction.

RESULTS

General characteristics

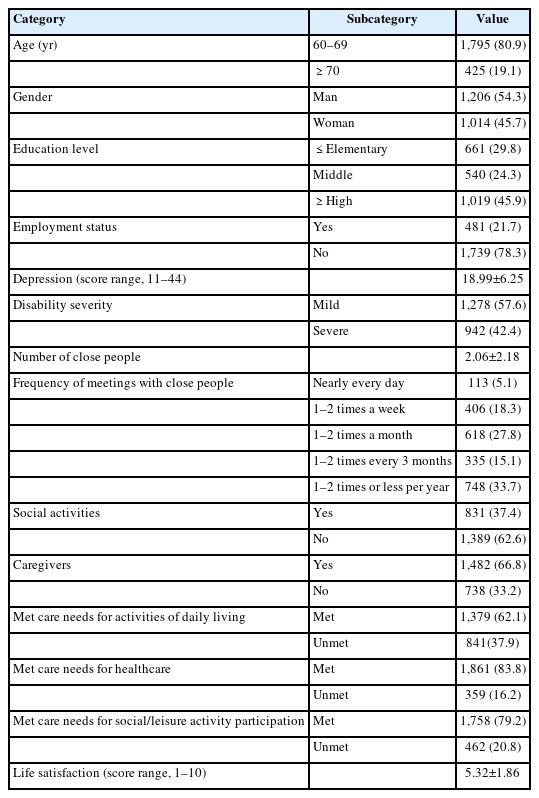

Among the participants, 54.3% were man, and 45.7% were woman. The highest proportion of participants (45.9%) were high school graduates or above. Approximately 78% of participants stated that they were not working at the moment. The average score of depression was 18.99, with 57.6% categorized as having mild disabilities. Regarding social factors, the average number of close persons was 2.06, and the most common frequency of meeting others was 1–2 times per year (33.7%). A total of 62.6% of participants responded that they did not engage in any social activities (Table 1).

Met care needs for living

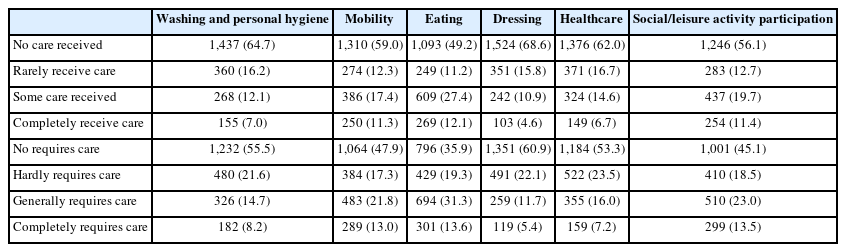

Approximately 66.8% of the participants reported having a caregiver. The prevalence of those who met ADL care needs was 62.1%. For health care and social/leisure activity participation, 83.8% and 79.2% of participants reported receiving sufficient care, respectively (Table 1). Table 2 displays the degree of care needed and the actual level of care received for daily living. Among ADL items, the care needs were highest for eating (44.9%) and social/leisure activity participation (36.5%), followed by mobility (34.8%). Similarly, ADL items that received the highest actual level of care were eating (39.5%), mobility (28.7%), and social/leisure activity participation (31.1%).

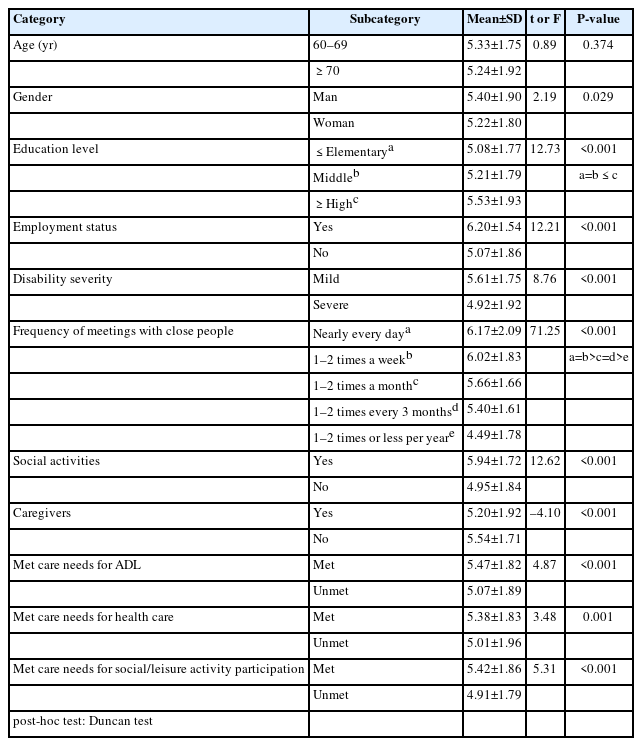

Life satisfaction

The average score of life satisfaction was 5.32 (Table 1). Differences in life satisfaction according to the general characteristics are as follows (Table 3). Significant differences were found in gender (t=2.19, P=0.029), education level (F=12.73, P<0.001), employment status (t=12.21, P<0.001), and disability severity (t=8.76, P<0.001). The frequency of meetings with close people (F=71.25, P<0.001) and social activity participation (t=12.62, P<0.001) were significantly related to life satisfaction.

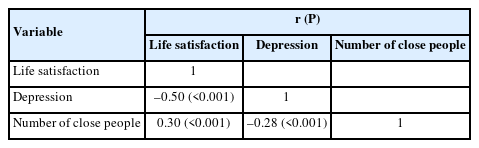

As for met care needs for living, having a caregiver (t=–4.10, P<0.001), met care needs for ADL (t=4.87, P<0.001), healthcare (t=3.48, P=0.001), and social/leisure activity (t=5.31, P<0.001) made significant differences in how satisfied older adults were with their lives (Table 3). Life satisfaction was negatively correlated with depression (r=–0.50, P<0.001). The number of close people was positively correlated with life satisfaction (r=0.30, P<0.001) (Table 4).

Factors influencing life satisfaction

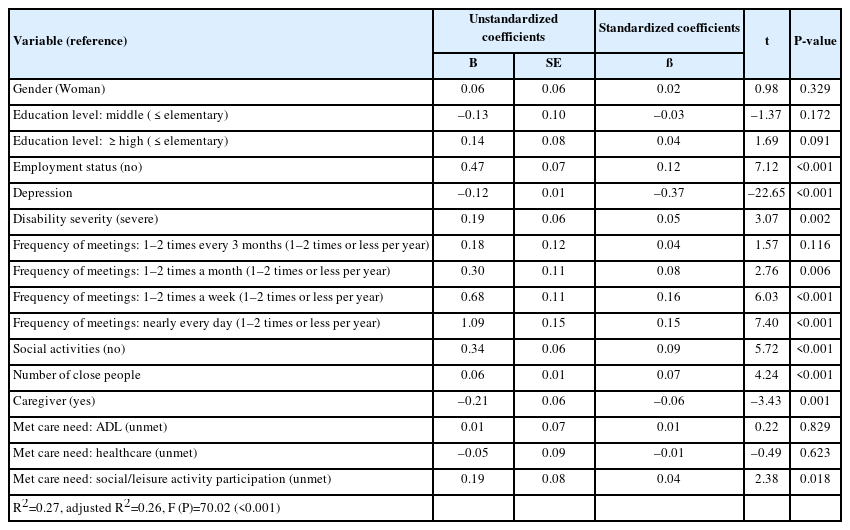

Multiple regression was used to identify factors influencing life satisfaction. This regression model explained 26% of the variance in quality of life. The variance inflation factor values ranged from 1.08 to 3.48, all of which were below 10. This indicates that no multicollinearity problems exist among the predictor variables. The multiple regression analysis revealed that meeting social/leisure activity care needs led to higher life satisfaction (ß=0.04, P=0.018). Having a job (ß=0.12, P<0.001), lower levels of depression (ß=–0.37, P<0.001), a higher number of close people (ß=0.07, P<0.001), more frequent meetings with them (almost daily meetings: ß=0.15, P<0.001), and engaging in social activities (ß=0.09, P<0.001) were all associated with higher life satisfaction (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

This study was conducted to assess the met care needs for living and the factors affecting the life satisfaction of older individuals with disabilities in the community. This study revealed that the life satisfaction of older adults with disabilities was 5.32 out of 10, indicating a moderate level. This result is similar to previous studies on the life satisfaction of older individuals with disabilities, which reported a score of 3.22 out of 5 [3], but lower than the life satisfaction score of non-disabled older adults, recorded at 3.6 out of 5 [15]. However, the participants were older adults aged 60 or older, so there is a limitation in directly comparing the results with those of studies conducted on older adults aged 64 or older.

Various factors, such as social support, depression, physical health, and the ability to perform ADL, influence life satisfaction [4]. Previous studies indicate that social relationships [4,6], depression [16], and the ability to perform ADL [5] are significant factors influencing life satisfaction. People with disabilities face an elevated risk of encountering not only physical function limits but also social isolation [11] and depression [12], which may adversely affect their overall life satisfaction. Therefore, providing more opportunities for social participation and emotional support is necessary to improve the life satisfaction of individuals with disabilities.

In this study, the life satisfaction of older adults with disabilities also showed significant differences based on social factors, employment status, and depression. Specifically, the study revealed that various social factors significantly influence the life satisfaction of disabled older adults. An increased number of close friends, neighbors, or acquaintances, along with regular interactions and engagement in social activities, correlates positively with life satisfaction. This finding is consistent with previous studies, which indicated that life satisfaction rises with the frequency of contact with friends, family, and neighbors [4,6,17]. Older adults often encounter a decline in social interactions and a decrease in social activities [10], and individuals with disabilities are more prone to experience greater social isolation compared to their non-disabled counterparts [11]. This study revealed a higher life satisfaction among those currently employed. Older adults view employment not only as an economic factor but also as a crucial element in enhancing social relationships [18]. Therefore, we expect older adults with disabilities to experience accelerated social isolation, which could lead to a higher risk of reduced life satisfaction. To improve life satisfaction, it is essential to provide tailored social participation programs for elderly individuals with disabilities and implement strategies to prevent social isolation by helping them maintain existing social relationships.

Furthermore, this study’s findings suggest a close relationship between met care needs for living are and overall life satisfaction. A significant difference in life satisfaction existed based on whether care needs for living were met or unmet. Participants who met their care needs for social/leisure activities, ADL, and healthcare demonstrated higher life satisfaction compared to those who did not. The availability of support for social/leisure participation was recognized as an important factor influencing life satisfaction.

The percentage of participants who needed care to participate in social or leisure activities was higher than those who actually received care. The rate of unmet care needs for participation in social/leisure activity was also high. There are few studies addressing the issue of met care needs. The findings were similar to the 27% unmet needs for social activities reported among community-dwelling older adults with dementia [19]. Such a high rate of unmet needs is likely to be a significant factor in reducing the life satisfaction of older individuals with disabilities.

As previously discussed, social participation plays a significant role in life satisfaction [2,20]. Enhancing their engagement in leisure activities or social participation could improve their life satisfaction. The fact that life satisfaction significantly increased when non-physical care, such as social/leisure participation, was adequately provided emphasizes the need for an integrated approach that supports overall living, not just physical care. This suggests that, in addition to meeting basic physical needs, social and emotional support play a crucial role in enhancing the life satisfaction of older individuals with disabilities.

Depression is an important influencing factor in this study. This shows similar results to previous studies, indicating that depression has an influence on life satisfaction [16]. This highlights the importance of managing depression in older adults. Since social activity support is known to play a key role in reducing depression [21], it would be crucial to promote social participation, which emerged as an important influencing factor in this study.

This study has several limitations. First, it did not consider the type of disability. Future research should examine the differences based on disability types and severity levels to identify factors influencing life satisfaction. Secondly, this study solely examined the existence or non-existence of a caregiver because it relied on secondary data. The quality of the relationship between caregivers and older adults may influence their life satisfaction, necessitating further research.

Additionally, we used secondary data in this study, categorizing the age in 10-year intervals. In this study, we defined older adults as over 60 years rather than over 65 years old. Comparing the findings of this study with those of other research presents a challenge. However, this study holds significance as it evaluates how the satisfaction of older adults with disabilities is influenced by their met care needs. Based on this study, the following recommendations are made: Firstly, we need to improve the quality of care for individuals. It is necessary to provide tailored support that reflects individual needs, going beyond physical assistance. In particular, care provision should focus not only on ADL but also on healthcare and social/leisure activity participation. Second, it is important to create an environment that fosters social relationships. We should activate community-based programs to prevent social isolation among older individuals with disabilities and strengthen their social networks. Furthermore, we should provide care to individuals who struggle with participation, ensuring their continued engagement in social activities for disabled older people.

Notes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Young KO had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors reviewed this manuscript and agreed to individual contributions.

Conceptualization: all authors. Formal analysis: SYH. Writing–original draft: YK. Writing–review & editing: all authors.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No existing or potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Public data was used, and the URL is https://koddi.or.kr/stat/html/user/main/main.