Association between Salty Taste Preference and Dietary Behaviors Related to Sugar Intake among Adults

Article information

Abstract

Background

Excessive sugar intake is a major global health concern, linked to elevated risks of obesity and various chronic diseases. Taste perception significantly influences dietary behaviors, yet the relationship between salty taste perception and sugar consumption remains underexplored. This study examines whether salty taste perception affects dietary behaviors related to sugar intake.

Methods

A total of 139 adults (35 males and 104 females) aged 19 and older participated. Salty taste recognition thresholds and preferences were evaluated using sensory tests involving salt solutions and soup samples with varying salt concentrations. Sugar-related dietary behaviors were assessed through a 10-item questionnaire survey and a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire consisted of 18 sweet-tasting foods.

Results

Younger adults displayed higher sugar-related dietary scores and consumed sweet-tasting foods more frequently than middle-aged participants. While salty taste recognition thresholds showed no significant association, salty taste preferences were positively correlated with sugar-related dietary behaviors. Participants with a stronger salty taste preference exhibited a greater tendency to consume sweetened foods and beverages and preferred sugar-rich foods such as jelly, cakes, and ice cream. These correlations remained significant after adjusting for sex and age, emphasizing the link between salty taste preference and total sugar intake. Male participants consumed sugar-sweetened beverages and sweet dishes, such as bulgogi, more often than females, though no sex differences were found in overall sugar-related dietary scores.

Conclusions

These findings highlight a close relationship between salty and sweet taste preferences, suggesting that individuals who prefer salty tastes may be more likely to increase their sugar intake. Understanding this interaction can help develop strategies to address excessive sugar consumption and its associated health risks.

INTRODUCTION

Excessive sugar intake has become a significant global public health issue. Epidemiological studies have shown strong associations between high sugar consumption and increased risks for various chronic diseases. For example, a meta-analysis reported that consuming 250 mL of sugar-sweetened beverages daily increases the risk of obesity by 12%, type 2 diabetes by 19%, and hypertension by 10% [1]. Additionally, a large prospective study involving a French cohort demonstrated a positive association between sugary drink consumption and the incidence of both breast cancer and overall cancer [2]. Moreover, higher intake of added sugars has been linked to an increased risk of all-cause mortality [3]. The metabolic effects of simple sugars, particularly fructose, further underline the health risks of excessive sugar consumption. Fructose is rapidly absorbed and metabolized, leading to metabolic disturbances such as insulin resistance, enhanced lipogenesis, and systemic inflammation [4].

Despite the well-documented health risks, sugar consumption has continued to rise in recent years. According to results from the recent Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES), the average daily sugar intake among Korean adults was 58.0 g [5], exceeding the World Health Organization’s recommendation of limiting sugar to less than 10% of daily caloric intake. Processed foods, particularly beverages, are the primary contributors to this increased intake, serving as major sources of added sugars [6]. Additionally, hidden sugars in processed foods such as bread, snacks, ice cream, and salad dressings further exacerbate daily sugar consumption. The ongoing rise in sugar intake and the negative health effects linked to high sugar consumption highlight the urgent need for effective strategies to reduce sugar consumption.

Taste perception plays an important role in one’s dietary habits and nutrient intake. For example, sensitivity to bitter taste is often associated with the avoidance of cruciferous vegetables and lower consumption of antioxidant nutrients [7]. Further, it was shown that differences in sensitivity to the bitter taste was associated with preferences for sucrose and sweet-tasting foods and beverages in children [8], indicating perceptions of different tastes can interact each other. Additionally, genetic variations in the T1R2/T1R3 receptors, which are responsible for the sweet taste, have been shown to affect sensitivity to both fat and sweet tastes, as well as obesity in Indians [9]. Little is known, however, whether there is an interaction between preferences for the salty taste and the sweet taste.

Previous studies on factors influencing sugar intake have primarily focused on children and adolescents [10,11]. However, as obesity rates rise and processed foods become more prevalent, sugar consumption and its related health risks have gained significant importance for adults. In this study, we aimed to examine dietary behaviors associated with sugar intake among adults aged 20 and older. We also explored the relationship between these dietary behaviors and the perception of salty taste.

METHODS

Study participants

This study was conducted among students and staff members of Kyung Hee University in Seoul, Korea, who provided written informed consent after receiving a detailed explanation of the study’s purpose, objectives, and procedures. Participants who had consumed alcohol within 24 hours prior to the sensory evaluation, as well as those who were pregnant or lactating, were excluded from the study. A total of 139 adults (35 males and 104 females) aged 19 years or older were included in the final analysis. Salty taste recognition thresholds and preferences were assessed through sensory evaluation. Dietary behaviors related to sugar consumption and the frequency of sweet-tasting food intake were collected using a survey questionnaire and a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire, respectively. Anthropometric data were also recorded. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Kyung Hee University (IRB No. KHSIRB-17-032(RA)).

Sensory evaluation

The salty taste recognition threshold was measured using a modified staircase method [12]. Twelve salt test solutions with concentrations ranging from 0.0045% to 0.3% were prepared and presented to participants in ascending order. If a participant detected a salty taste in two consecutive samples, the lower concentration of the two samples was recorded as the recognition threshold.

To assess salty taste preference, participants were asked to choose their preferred salt concentration in a clear soup made with soybean sprouts. Five soup samples were prepared with salt concentrations of 0.08%, 0.16%, 0.32%, 0.63%, and 1.25% [13]. The samples were presented in random order, and participants selected their preferred concentration after tasting each sample for approximately 10 seconds. All participants were instructed to abstain from alcohol for 24 hours and to avoid consuming food or brushing their teeth for at least 2 hours before the sensory evaluation.

Dietary assessment

Dietary behaviors related to sugar consumption were evaluated using a questionnaire comprising 10 items, based on Lee [14]. Participants responded on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicated a stronger tendency toward sweet eating behaviors. One question, ‘I check the nutrition label for sugar content when I buy processed foods’, was reverse-coded before calculating total scores. The maximum possible score was 50.

The frequency of sweet-tasting food consumption was assessed using a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire developed based on a previous studies [14,15]. The questionnaire included 18 sweet-tasting foods categorized into six food groups. Participants recalled their weekly consumption frequency for each food over the past year, with frequency categories ranging from 0 (never) to 7 (seven times per week).

General and anthropometric characteristics

Anthropometric measurements, including height and weight, were obtained by trained staff. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2), with a BMI range of 18.5 to 23.0 kg/m2 classified as normal. General characteristics such as age, sex, alcohol consumption, and smoking status were collected via a survey questionnaire. Participants were divided into young adults (20–29 years) and middle-aged adults (30–69 years) based on their age.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean±standard deviation, while categorical variables were expressed as number (%). Differences in salty taste thresholds, preferences, and dietary behaviors by sex or age were analyzed using the Student’s t-test or χ2-test. Partial correlation analysis, adjusted for sex and age, was used to assess associations between salty taste thresholds and preferences, sugar-related dietary behaviors, and sweet-tasting food intake. Statistical analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (ver. 4.4.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing), with a P-value <0.05 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

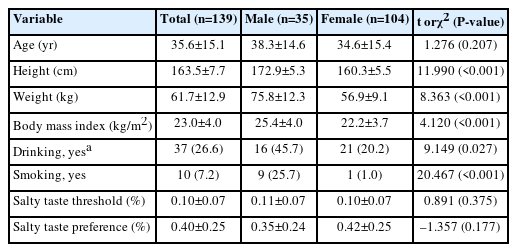

General characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1. Among the 139 study participants, 55.4% were in their 20s, with a mean age of 35.6 years. Male participants comprised 25% of the total study participants, and there was no significant difference in mean age between the sexes. The mean BMI was 23.0 kg/m2, and 47.5% of participants were within the normal weight range. Additionally, 7.2% of participants were current smokers, and 26.6% reported consuming alcohol at least once a week. The mean salty taste recognition thresholds for males and females were 0.11% and 0.10%, respectively; however, the difference between sexes was not statistically significant (Table 1).

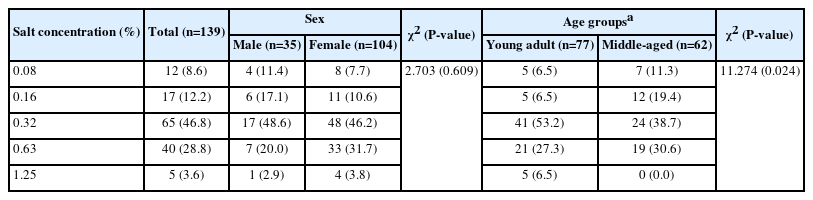

The salty taste preferences of the study participants, stratified by sex and age groups, are shown in Table 2. Among the five different salt concentrations of bean sprout soup, 0.32% was the most preferred concentration in both sexes (48.6% in males and 46.2% in females), followed by 0.63% (20.0% in males and 31.7% in females). No statistically significant difference in salty taste preference was observed between the sexes. However, a significant difference in salty taste preference was observed between age groups. Specifically, 53.2% of participants in the young adult group preferred the soup with a salt concentration of 0.32%, compared to 38.7% of participants in the middle-aged group. Additionally, 19.4% of participants in the middle-aged group preferred the soup with a salt concentration of 0.16%, whereas only 6.5% of participants in the young adult group showed a preference for this concentration.

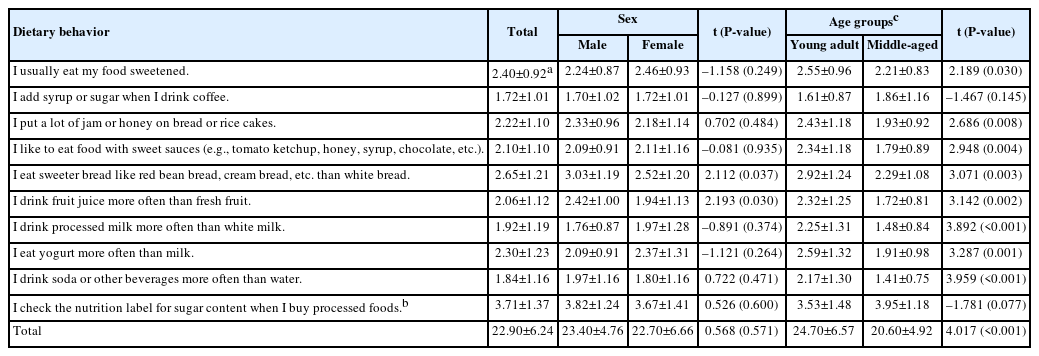

We evaluated participants’ dietary behaviors concerning sugar consumption using a 10-item questionnaire, with each item rated on a 5-point Likert scale. The results showed no significant differences in total scores (the sum of all 10 items) between the sexes (Table 3). However, significant differences were found for two specific items: ‘I eat sweeter bread like red bean bread, cream bread, etc. than white bread’, and ‘I drink fruit juice more often than fresh fruit’ (P<0.05). In contrast, notable differences were evident across age groups. The total dietary behavior scores related to sugar consumption were significantly higher in the young adult group compared to the middle-aged group (24.70 vs. 20.60, respectively, P<0.001). Furthermore, scores for eight out of the 10 items were significantly higher in the young adult group than in the middle-aged group, highlighting age-related differences in dietary behaviors regarding sugar consumption.

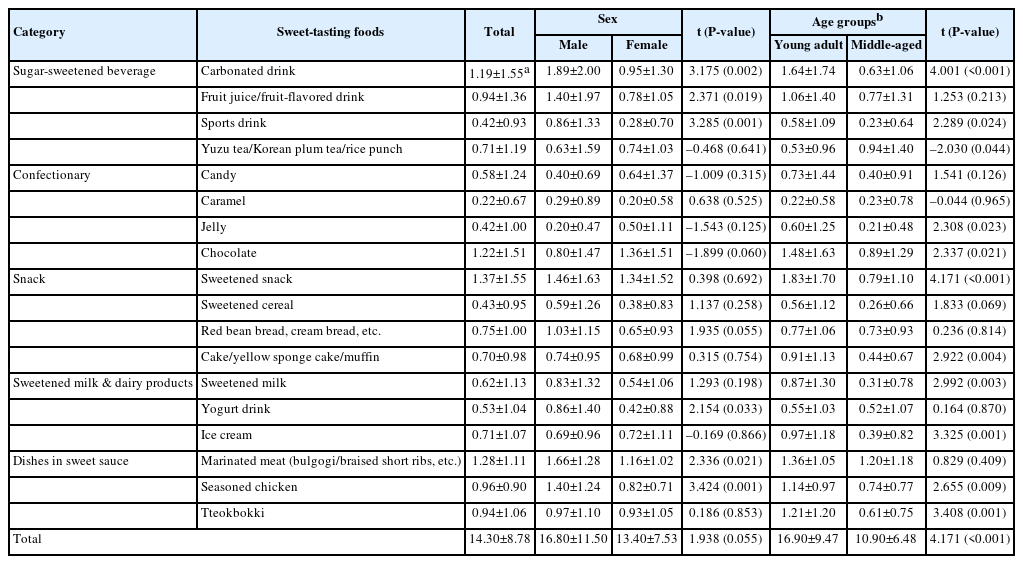

Next, the consumption frequency of sweet-tasting foods was evaluated using a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire (Table 4). Male participants reported consuming sugar-sweetened beverages—such as carbonated drinks, fruit juices/fruit-flavored juices, and sports drinks—more frequently than female participants. For example, the frequency of carbonated drinks consumption among males was approximately twice that of females (1.89 times/wk vs. 0.95 times/wk, respectively). Similarly, males consumed sports drinks nearly three times more often than females (0.86 times/wk vs. 0.28 times/wk, respectively). Additionally, male participants consumed dishes in sweet sauces, such as bulgogi and seasoned chicken, significantly more frequently than female participants. Conversely, no significant differences were found between males and females in the consumption frequencies of confectionaries, snacks, sweet breads, or sweetened milk and dairy products except for yogurt drink.

When comparing age groups, the young adult group consumed most sweet-tasting foods more frequently than the middle-aged group. Significant differences in consumption frequencies between the age groups were observed for carbonated drinks, sports drinks, yuza tea/Korean plum tea/rice punch, sweetened snacks, jelly, chocolate, cake/yellow sponge cake/muffin, sweetened milk, ice cream, seasoned chicken, and tteokbokki. The total frequency of sweet-tasting food consumption in the young adult group was 16.90 times per week, significantly higher than the middle-aged group, which had a consumption of 10.90 times per week (P<0.001).

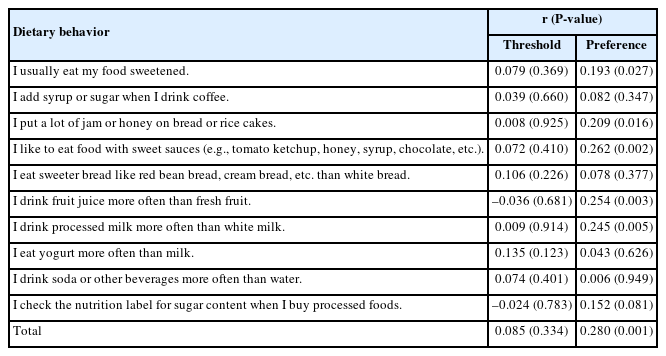

To investigate whether salty taste preference or salty taste threshold is associated with dietary behaviors related to sugar consumption, correlation analyses were conducted while adjusting for sex and age (Table 5). Among the dietary behaviors related to sugar consumption, several items showed a positive correlation with salty taste preference, including: ‘I usually eat food sweetened’, ‘I put a lot of jam or honey on bread or rice cakes’, ‘I like to eat food with sweet sauces (e.g., tomato ketchup, honey, syrup, chocolate, etc.)’, ‘I drink fruit juice more often than fresh fruit’, and ‘I drink processed milk more often than white milk’. Furthermore, the total score of dietary behaviors related to sugar consumption was positively correlated with salty taste preference, suggesting that a stronger preference for salty tastes is associated with higher sugar consumption. In contrast, no significant relationship was observed between the salty taste threshold and dietary behaviors related to sugar consumption.

Correlation of salty taste threshold and salty taste preference with dietary behaviors related to sugar consumption

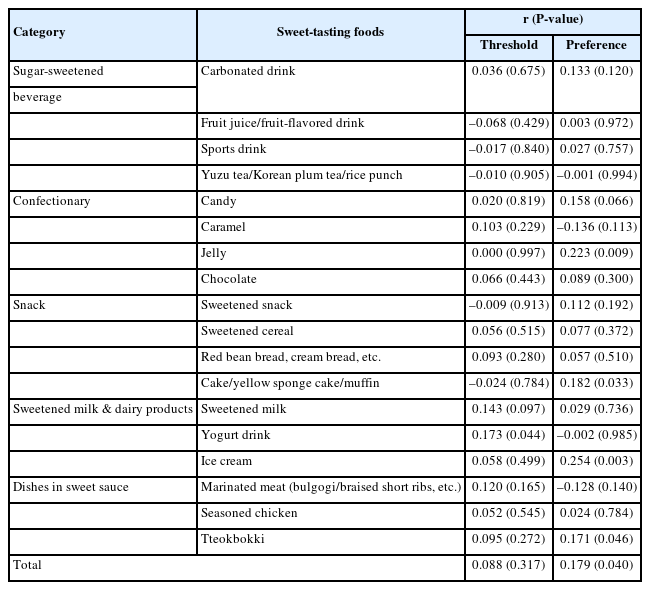

We also analyzed the correlation of salty taste preference and threshold with the consumption frequency of sweet-tasting foods, adjusted for sex and age (Table 6). Salty taste preference was positively correlated with the consumption of specific sweet-tasting foods, including jelly, cake/yellow sponge cake/muffins, ice cream, and tteokbokki. The salty taste threshold, however, was not significantly correlated with any sweet-tasting foods, except for yogurt drink. Furthermore, the preference for salty taste, but not threshold was positively associated with the total frequency of sweet-tasting food consumption, even after adjusting for sex and age (r=0.179, P=0.040). These findings underscore the potential influence of salty taste preference on sugar consumption behaviors.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated dietary behaviors associated with sugar consumption and the frequency of sweet-tasting food intake among adults, stratified by sex and age groups. Additionally, we examined the correlation between salty taste recognition thresholds and preferences with sugar-related dietary behaviors and the frequency of sweet-tasting food intake. The findings revealed that age exerted a stronger influence on dietary behaviors related to sugar consumption and sweet-tasting food intake than sex. Specifically, young adults demonstrated a greater tendency to pursue and consume sweet-tasting foods compared to middle-aged individuals. Moreover, a higher preference for salty taste was significantly associated with elevated scores in dietary behaviors related to sugar consumption and more frequent sweet-tasting food intake. These results suggest a close link between a preference for salty taste and increased sugar consumption.

In this study, we demonstrated that salty taste preferences significantly influenced dietary behaviors related to sugar consumption, even after controlling for sex and age. Additionally, we found that a preference for salty taste was associated with the frequent consumption of sugar-rich snacks such as jelly, ice cream, and cake, likely contributing to increased overall sugar intake. This aligns with a recent study showing that habitual salt intake was positively correlated with more frequent consumption of sugar-containing foods among middle-school students [16]. Similarly, a study conducted in the US involving healthy children and their mothers [17] reported that the most preferred sucrose concentrations in water were significantly associated with the most preferred salt levels in broth for both children and mothers. Furthermore, dietary intake of added sugars was positively correlated with sodium intake. These findings corroborate our results, highlighting a strong relationship between salty taste preference and sugar consumption. They also suggest that modifying salty taste preferences may be an effective strategy for reducing sugar intake in adults.

In this study, we assessed participants’ sensitivity to salty taste by measuring recognition thresholds using various concentrations of salt solutions. Interestingly, unlike the relationship observed with salty taste preference, no significant association was found between salty taste sensitivity and dietary behaviors related to sugar consumption. Taste acuity is known to be influenced by genetic predisposition [12,18-20] and may not directly correlate with taste preference [21]. For instance, frequent consumption of high-salt fast foods has been shown to enhance preferences for salty taste [22], suggesting that taste preferences are more closely linked to dietary habits than genetic factors.

The precise mechanism by which salty taste influences sugar intake remains unclear. Recent research by Yasumatsu et al. [23] identified a transduction pathway independent of the sweet taste receptor T1R2/T1R3 heterodimer. They demonstrated that a sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 (SGLT1) expressed in the apical membrane of sweet-sensitive taste cells plays a key role in detecting glucose-containing sugars in mice. Further research is needed to determine whether sodium-dependent sugar sensing mediated by SGLT1 also contributes to sweet taste perception in humans.

The assessment of salty taste thresholds and preferences using sensory testing in this study provides valuable insights as a proxy indicator for salt intake within populations. Although urinary sodium excretion is regarded as the gold standard for evaluating salt intake, its application is often limited in community-based studies due to its high cost and participant burden. Previous studies have shown that taste sensitivity and preferences can serve as reliable indirect markers for habitual dietary intake patterns [24,25], offering a feasible alternative for large-scale assessments. Similarly, the evaluation of dietary behaviors related to sugar consumption in this study provides valuable insights for estimating sugar intake. Direct measurement of sugar intake is challenging, primarily due to inaccuracies in nutrient databases, particularly concerning the sugar content of processed foods [26]. Consequently, dietary behavior questionnaires that are closely correlated with sugar consumption offer a practical and potentially more effective alternative for estimating sugar intake in population-based studies.

In our study, dietary behaviors related to sugar consumption and the frequency of sweet-tasting food intake were notably higher among the young adult group compared to the middle-aged group. In alignment with these findings, a recent study reported that the prevalence of US adults aged ≥19 years consuming more than 15% of total calories from added sugars was significantly lower among those aged ≥71 years compared to younger age groups [27]. The mean age of the middle-aged group in our study was 50.5 years, while that of the young adult group was 23.5 years. These results suggest that sugar consumption begins to decline earlier in adulthood, well before reaching older age. Supporting this, data from the KNHANES [5] revealed that the intake of sugar and its products is highest among adults in their 20s (11.3 g), gradually decreasing to 9.7 g, 8.0 g, and 5.8 g for individuals aged 30–49 years, 50–64 years, and ≥65 years, respectively.

Further, Lampuré et al. [28] found that age is inversely associated with a strong preference for sweet taste among French adults and reported that eating behaviors, such as cognitive restraint, uncontrolled eating, and emotional eating, also influence sweet taste preferences in both males and females. However, the relationship between sugar consumption and sex remains less clear, with conflicting results across studies [29]. In our study, the total scores for dietary behaviors related to sugar consumption did not differ significantly between males and females, although two out of ten questionnaire items scored higher among males. Certain types of foods, such as sugar-sweetened beverages, appear to be consumed more frequently by males than females, as observed in other studies [30,31].

The limitation of this study is the relatively small number of participants. However, the use of sensory evaluation to assess taste thresholds and preferences offers a significant advantage over large-scale surveys, which are unable to employ such measurements. Additionally, the inclusion of male and female participants spanning an age range from their 20s to their 60s provides a comprehensive perspective on salty taste preferences and their relationship to sugar intake across diverse demographic groups.

Further research is required to evaluate the impact of increased sugar intake associated with salty taste preferences on specific health parameters, such as BMI, blood lipid profiles, and other metabolic markers.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated a significant association between salty taste preference and dietary behaviors related to sugar consumption in adults. The findings provide valuable evidence of the interconnected nature of salty and sweet eating behaviors. These results could serve as a foundation for designing effective nutritional education strategies targeting adults, fostering a more integrated and efficient approach to modifying dietary behaviors and promoting healthier eating habits.

Notes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Jayong CHUNG had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors reviewed this manuscript and agreed to individual contributions.

Conceptualization: JC. Methodology & Formal analysis: MN. Writing–original draft: MN and MY. Writing–review & editing: all authors.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No existing or potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

FUNDING

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korean Government (MIST) (NRF-2020R1F1A1075611).

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data presented in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.