Assessment of Weight Change and All-Cause Mortality Based on Body Mass Index Intervals in South Korea: A 12-Year Follow-Up of the Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging

Article information

Abstract

Background

Obesity and weight loss are associated with increased mortality. Understanding the association between weight change and mortality is critical and can help inform effective prevention and intervention strategies. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the association between weight change and mortality based on body mass index (BMI) intervals using data from a 12-year follow-up survey in Korea.

Methods

We used data from the Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging from 2006 to 2018. Individuals aged 45–69 years without a history of malignancy and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at baseline were selected. Cox regression analysis was used to compare mortality based on body mass index and weight change.

Results

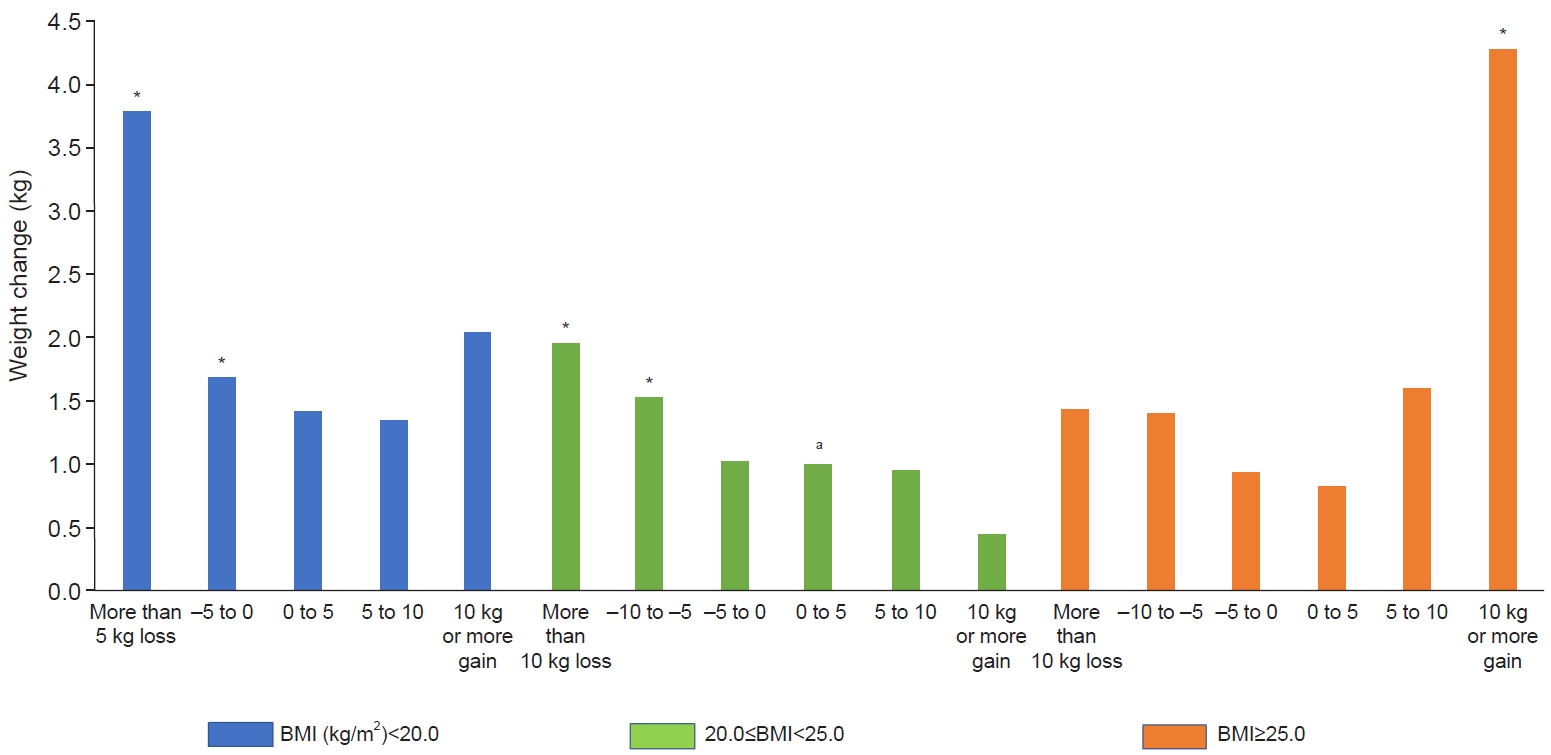

Compared with individuals with a body mass index of 20.0–25.0 kg/m2 and an increase in body weight of <5 kg, mortality was 3.8 times higher in the group with a body mass index of <20.0 kg/m2 and a weight loss of <5 kg, two times higher in the group with a body mass index of 20.0–25.0 kg/m2 and weight loss of >10 kg, and 4.3 times higher in the group with a body mass index of ≥25.0 kg/m2 and weight gain of ≥10 kg.

Conclusions

Weight loss in underweight or normal-weight individuals and weight gain in individuals with obesity increased the mortality rate compared with individuals with normal weight and less weight change. This suggests that body weight and the changes in the weight of individuals are crucial, and weight loss in patients with underweight and weight gain in patients with obesity are closely related to increased mortality.

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is a chronic disease increasing worldwide, and its prevalence has doubled since 1980 in more than 70 countries and has continued to rise across other nations [1]. Obesity is a risk factor for other chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, cardiovascular disease, and various cancers [2-4]. Therefore, many countries have emphasized the research on their obesity rates and implementing policies to reduce them.

Currently, obesity is classified based on body mass index (BMI) (weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), overweight in adults is defined as a BMI of ≥25 kg/m2 and obesity as a BMI of ≥30.0 kg/m2 [5]. In contrast, overweight in the adult population of the Asia-Pacific region is defined as a BMI of ≥23.0 kg/m2 and obesity as a BMI of ≥25.0 kg/m2 [6]. This lower categorization in the Asia-Pacific region is due to a higher prevalence of chronic diseases in individuals who are classified as overweight based on the WHO BMI definition. Additionally, underweight is defined as a BMI of <18.5 kg/m2, and this is based on data indicating a slight increase in comorbidities in this BMI population [6]. Notably, criteria for obesity or underweight to date have been based on the presence of comorbidities.

Studies examining the association between BMI and mortality have revealed different results. A meta-analysis reported the lowest mortality in individuals with a BMI of 27.0–27.9 kg/m2 in Europe and America [7]. However, in Asia, the lowest mortality rate was reported for individuals with a BMI of 23.0–24.9 kg/m2 [8,9]. According to the Asian standards, a BMI between 23.0 kg/m2 and 24.9 kg/m2 is considered overweight. The data, therefore, suggest that people who are overweight or obese are less likely to die than those of normal weight.

Although the association between BMI and increased mortality risk is well established, intentional and unintentional weight loss and weight gain have been associated with higher mortality rates, thus indicating that weight change is related to mortality. In a meta-analysis of 26 prospective studies, unintentional weight loss was associated with higher mortality (risk ratio, 1.22; 95% confidence interval, 1.09–1.37; P=0.001) [10]. In another meta-analysis, increased risk for all-cause mortality was 67% with weight loss, 21% with weight gain, and 53% with weight fluctuation among adults 60 years and older [11]. In a Korean study, weight loss hazard ratio (HR)= 1.68 (1.65–1.72) and weight gain HR=1.10 (1.07–1.13) were compared with stable weight [12].

The relationship between weight change and mortality has important implications for public health policy and clinical practice, and the effects of weight gain in underweight and weight loss in overweight on mortality are expected to be complex. Understanding the association between weight change and mortality according to BMI intervals can help inform effective prevention and intervention strategies. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effect of weight change on mortality based on BMI intervals.

METHODS

We used the data from the Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging (KLoSA), which is a 12-year cohort survey that has been followed up since 2006 to prepare for the aging population [13]. The survey was delivered to 10,254 individuals aged ≥45 years residing in areas of South Korea other than Jeju Island. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Keimyung University (IRB No: 2021-08-115). This survey has been performed with the appropriate participants’ informed consent in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration. Data were collected through computer-assisted personal interviewing. In this method, the interviewer brings a laptop computer, reads the questions displayed on the computer screen to the participants, and then directly inputs their responses using the keyboard or mouse. In the survey, biological personal data, spouse information, social information, family information, health and ecological information, and medical insurance and labor information were recorded over 83 variables. In cases of death, the date and cause of death were investigated from the family members or acquaintances. The survey participants were followed up every 2 years from 2006. The latest survey data published was after the seventh follow-up in 2018.

We extracted data on death, BMI, medical history, exercise, smoking, and alcohol consumption from the KLoSA data for analysis. We selected individuals aged 45–69 years old with no history of malignancy and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at the beginning of the study.

Categorical variables were analyzed using the χ2 test and presented as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were analyzed using the independent t-test and presented as means and standard deviations. Cox regression analysis was used to compare mortality. Two-sided P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23.0 software (IBM Corp.).

RESULTS

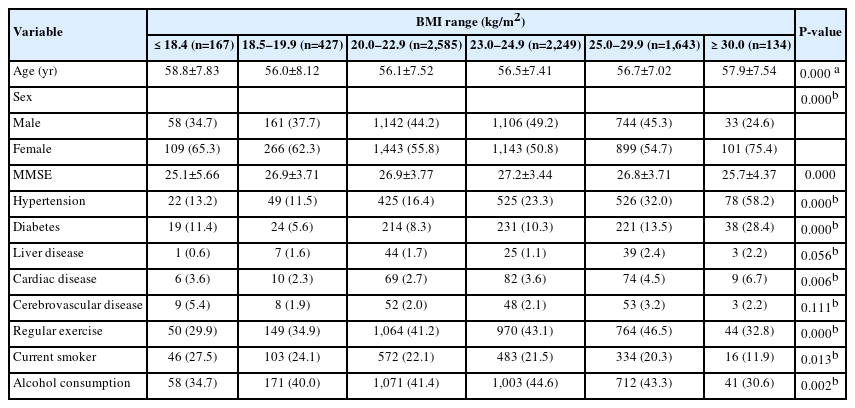

A total of 7,205 participants aged 45–69 years without a history of malignancy and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in 2006 were included. The average age of the sample was 57 years, with 3,244 male and 3,961 female. There were 167 underweight participants with a BMI of <18.5 kg/m2, 427 participants with a BMI of 18.5–19.9 kg/m2, 2,585 participants with a BMI of 20.0–22.9 kg/m2, 2,249 participants with a BMI of 23.0–24.9 kg/m2, 1,643 participants with a BMI of 25.0–29.9 kg/m2, and 134 participants with a BMI ≥30.0 kg/m2. Among those with a BMI of 18.5–19.9 kg/m2, the youngest participant was 56.0 years old, whereas among those with a BMI <18.5 kg/m2, the oldest participant was 58.8 years old. The rates of hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease were highest in individuals with a BMI of ≥30.0 kg/m2, and cerebrovascular disease accounted for the highest proportions in those with a BMI of <18.5 kg/m2. The proportion of individuals who exercised regularly was the highest among the BMI of 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 group. The smoking rate was the highest among those with a BMI of <18.5 kg/m2, and the drinking rate was the highest among those with a BMI of 23.0–24.9 kg/m2 (Table 1).

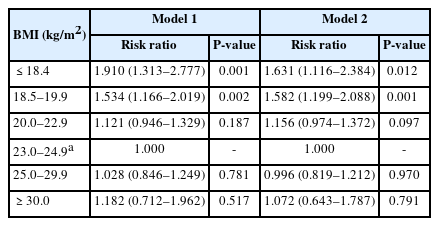

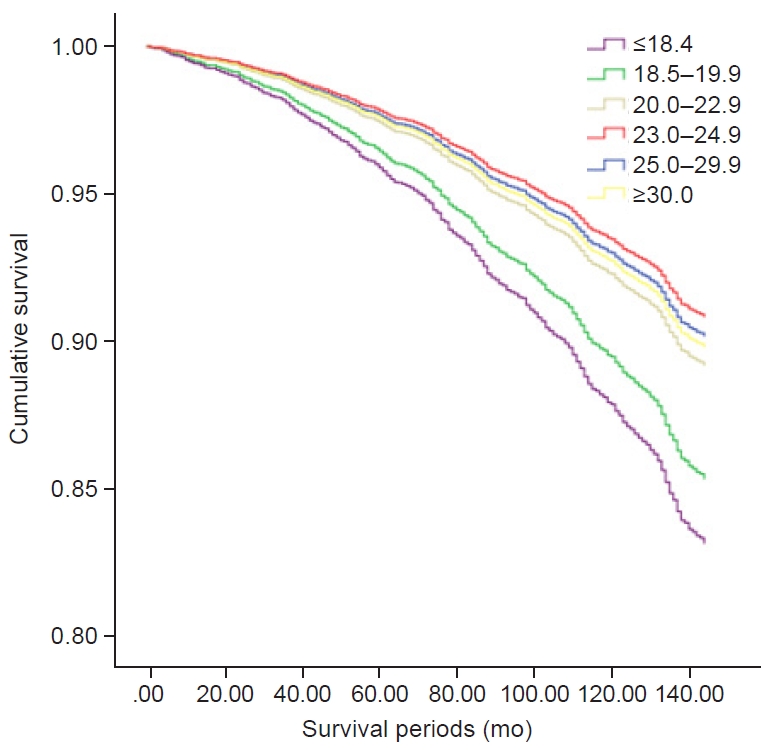

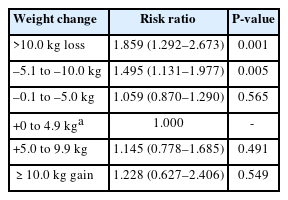

A total of 830 individuals died during the follow-up period through to 2018. Compared with the participants with a BMI of 23.0–24.9 kg/m2, mortality was 1.9 times higher for individuals with a BMI of <18.5 kg/m2 and 1.5 times higher for those with a BMI of 18.5–19.9 kg/m2 (Table 2). Mortality was 1.9 times higher in the group with a weight loss of >10 kg during the first 2 years than in the group with a weight gain of <5 kg. Additionally, mortality was 1.5 times higher in the group with a weight loss of 5.1–10 kg in the first 2 years than in the group with a weight gain <5 kg (Table 3).

Cox regression analysis for mortality according to weight change for first 2 years (10 years follow-up)

The HR according to BMI interval was highest in the group with a BMI of <18.5 kg/m2 and lowest in the group with a BMI of 23.0–24.9 kg/m2 (Fig. 1). Compared with the group with a BMI of 20.0–25.0 kg/m2 and an increase in body weight of <5 kg, mortality was 3.8 times higher in the group with a BMI of <20.0 kg/m2 and a weight loss of >5 kg and 1.7 times higher in the group with a BMI of <20.0 kg/m2 and weight loss of 0.1–5.0 kg. Mortality was two times higher in the group with a BMI of 20.0–25.0 kg/m2 and weight loss of >10 kg and 1.5 times higher in the group with a BMI of 20.0–25.0 kg/m2 and weight loss of 5.1–10.0 kg compared with the group with a BMI of 20.0–25.0 kg/m2 and an increase in weight of <5 kg. Mortality was 4.3 times higher in the group with a BMI of ≥25.0 kg/m2 and weight gain of ≥10 kg compared with the group with a BMI of 20.0–25.0 kg/m2 and an increase in body weight of <5 kg (Fig. 2).

DISCUSSION

In our study, the BMI range with the lowest comorbidity was 18.5 to 19.9 kg/m2. This is consistent with the existing data [6]. In the normal BMI group, the prevalence of comorbidities was the lowest, with comorbidities increasing with a decrease or increase in BMI. However, the overweight group (according to the Asian-Pacific WHO classification; BMI, 23.0–24.9 kg/m2) had the lowest mortality, with mortality increasing with a decrease or increase in BMI. This result is consistent with results in other studies conducted on other races in Asia. In a Japanese cohort study conducted from 1990 to 1999, individuals with a BMI of 23.0–24.9 kg/m2 had the lowest mortality [9], which is also consistent with a prospective study in China, wherein the mortality was lowest among individuals with a BMI of 21.0–23.5 kg/m2 [14].

Within the normal BMI range, the mortality in the group with a BMI of 18.5–19.9 kg/m2 was 1.5 times higher than that in the group with a BMI of 23.0–24.9 kg/m2. This suggests that attention should be paid to the high mortality in people with extreme BMIs and people with normal BMI of <20.0 kg/m2.

In addition, we investigated the relationship between body weight change in 2 years and mortality over a 10-year follow-up as a post-hoc analysis to determine how changes in body weight affect mortality. The mortality increased more with weight loss than with weight gain. Mortality was 1.5 times higher in the group in which individuals lost 5.1–10.0 kg compared with the group in which individuals gained 0–5 kg. Mortality was also increased by 1.9 times in the group in which individuals lost ≥10 kg. This suggests that weight loss and being underweight are risk factors for death. To better understand these results, we divided BMI into three groups and then investigated the relationship between weight change and mortality in each BMI group (Fig. 2). In the group with a BMI of <20.0 kg/m2, a statistically significant increase was observed in the mortality rate of all the individuals who lost weight. In the group with a BMI of ≥25.0 kg/m2, the mortality rate was increased in individuals who gained ≥10 kg. In the group with a BMI of 20.0–25.0 kg/m2, mortality was increased in those who lost ≥5.1 kg. These results suggest that, in Asian populations, weight loss increases the risk of death in individuals with a BMI <25.0 kg/m2, and weight gain increases the risk of mortality in those with a BMI ≥25 kg/m2.

In general, weight decreases with increasing age in older adults [15]. Previous studies have shown that weight loss in older adults is associated with cancer, chronic disease, thyroid disease, gastrointestinal disease, and mental illness, which are associated with increased mortality [16,17]. Additionally, low BMI and weight loss are closely associated with sarcopenia, which is further associated with mortality [18-22]. After middle age, weight loss can cause loss of muscle mass, which may increase mortality [23]. People within the normal range of BMI are usually not advised to change their weight. In underweight individuals, the mortality rate increased with either a decrease or increase in weight, and the mortality rate exhibited an increasing trend, although this was not statistically significant. These results may differ depending on whether there is an actual muscle mass increase or only a fat increase upon weight gain. Further research is needed to determine the effects of weight gain with increasing muscle mass on mortality in underweight individuals.

In our study, individuals with a BMI of ≥25.0 kg/m2 exhibited a high mortality rate, but it was not statistically significant. However, excessive weight gain in the group with high BMI increased their mortality rate. These results are consistent with those of other studies involving Asians, implying that excessive weight gain in patients with obesity should be avoided [12,24].

The present study has some limitations. First, death data from the KLoSA was based on the memory of close family members and relatives; therefore, the date of death may not be accurate. Additionally, we cannot distinguish whether weight loss was intentional or unintentional. Notably, unintentional weight loss can be more dangerous than intentional weight loss [25]. Moreover, there are many diseases that can cause sarcopenia, including heart failure, tuberculosis, and thyroid disease, but our data did not include data on these conditions, so we were unable to control for confounding by these diseases. Therefore, further research is necessary to prove this hypothesis.

Despite these limitations, this study had strengths. KLoSA is a nation-wide dataset of 10,254 individuals aged ≥45 years, and this data was long-term, tracked for 12 years (2006–2018), thus providing credibility to the long-term effects of weight change on mortality.

Conclusion

This study revealed that weight loss in underweight individuals or those with normal weight and weight gain in overweight individuals increased their risk of mortality compared with individuals with normal weight and less weight change. This suggests that, in addition to body weight, changes in the weight of an individual are crucial, and weight loss in underweight patients or weight gain in patients with obesity are closely related to increased mortality. Obesity remains an important issue for community health. Paying increased attention to low body weight and weight loss among individuals is imperative to enhance healthcare in local communities.

Notes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Seung Wan HONG had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors reviewed this manuscript and agreed to individual contributions.

Conceptualization: SWH. Data curation: SWH. Formal analysis: SWH. Funding acquisition: SWH. Investigation: SWH. Methodology: SWH. Project administration: SWH. Resources: SWH. Supervision: JHL. Writing–original draft: DHC. Writing–review & editing: JHL, SWH, YSS, and DHK.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No existing or potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data presented in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.