| Korean J Health Promot > Volume 24(3); 2024 > Article |

|

ABSTRACT

Background

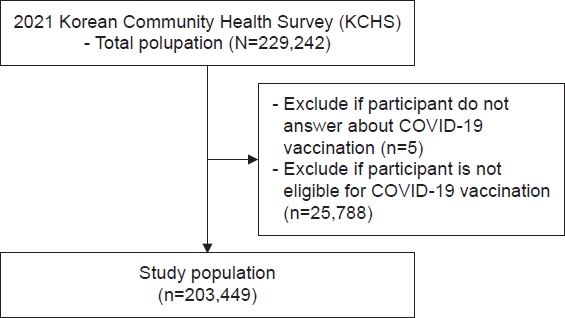

Methods

Results

Conclusions

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Sung SUNWOO had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors reviewed this manuscript and agreed to individual contributions.

Conceptualization: YHL and SEP. Data curation: YHL and SEP. Formal analysis: YHL and SEP. Investigation: YHL. Methodology: YHL. Software: YHL. Validation: YHL. Writing–original draft: YHL. Writing–review & editing: SS.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No existing or potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Table 1.

Table 2.

Table 3.

Table 4.

REFERENCES

-

METRICS

-

- 1 Crossref

- 0 Scopus

- 1,281 View

- 13 Download

- ORCID iDs

-

Yong Ho LEE

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5056-6393Seong-Eon PARK

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9224-2979Sung SUNWOO

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0521-4804 - Related articles

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print